Datalink layer technologies

Contents

Datalink layer technologies¶

In this section, we review the key characteristics of several datalink layer technologies. We discuss in more detail the technologies that are widely used today. A detailed survey of all datalink layer technologies would be outside the scope of this book.

The Point-to-Point Protocol¶

Many point-to-point datalink layers 1 have been developed, starting in the 1960s. In this section, we focus on the protocols that are often used to transport IP packets between hosts or routers that are directly connected by a point-to-point link. This link can be a dedicated physical cable, a leased line through the telephone network or a dial-up connection with modems on the two communicating hosts.

The first solution to transport IP packets over a serial line was proposed in RFC 1055 and is known as Serial Line IP (SLIP). SLIP is a simple character stuffing technique applied to IP packets. SLIP defines two special characters : END (decimal 192) and ESC (decimal 219). END appears at the beginning and at the end of each transmitted IP packet and the sender adds ESC before each END character inside each transmitted IP packet. SLIP only supports the transmission of IP packets and it assumes that the two communicating hosts/routers have been manually configured with each other’s IP address. SLIP was mainly used over links offering bandwidth of often less than 20 Kbps. On such a low bandwidth link, sending 20 bytes of IP header followed by 20 bytes of TCP header for each TCP segment takes a lot of time. This initiated the development of a family of compression techniques to efficiently compress the TCP/IP headers. The first header compression technique proposed in RFC 1144 was designed to exploit the redundancy between several consecutive segments that belong to the same TCP connection. In all these segments, the IP addresses and port numbers are always the same. Furthermore, fields such as the sequence and acknowledgment numbers do not change in a random way. RFC 1144 defined simple techniques to reduce the redundancy found in successive segments. The development of header compression techniques continued and there are still improvements being developed now RFC 5795.

While SLIP was implemented and used in some environments, it had several limitations discussed in RFC 1055. The Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) was designed shortly after and is specified in RFC 1548. PPP aims to support IP and other network layer protocols over various types of serial lines. PPP is in fact a family of three protocols that are used together :

The Point-to-Point Protocol defines the framing technique to transport network layer packets.

The Link Control Protocol that is used to negotiate options and authenticate the session by using username and password or other types of credentials

The Network Control Protocol that is specific for each network layer protocol. It is used to negotiate options that are specific for each protocol. For example, IPv4’s NCP RFC 1548 can negotiate the IPv4 address to be used, the IPv4 address of the DNS resolver. IPv6’s NCP is defined in RFC 5072.

The PPP framing RFC 1662 was inspired by the datalink layer protocols standardized by ITU-T and ISO. A typical PPP frame is composed of the fields shown in the figure below. A PPP frame starts with a one byte flag containing 01111110. PPP can use bit stuffing or character stuffing depending on the environment where the protocol is used. The address and control fields are present for backward compatibility reasons. The 16 bit Protocol field contains the identifier 2 of the network layer protocol that is carried in the PPP frame. 0x002d is used for an IPv4 packet compressed with RFC 1144 while 0x002f is used for an uncompressed IPv4 packet. 0xc021 is used by the Link Control Protocol, 0xc023 is used by the Password Authentication Protocol (PAP). 0x0057 is used for IPv6 packets. PPP supports variable length packets, but LCP can negotiate a maximum packet length. The PPP frame ends with a Frame Check Sequence. The default is a 16 bits CRC, but some implementations can negotiate a 32 bits CRC. The frame ends with the 01111110 flag.

PPP frame format¶

PPP played a key role in allowing Internet Service Providers to provide dial-up access over modems in the late 1990s and early 2000s. ISPs operated modem banks connected to the telephone network. For these ISPs, a key issue was to authenticate each user connected through the telephone network. This authentication was performed by using the Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP) defined in RFC 3748. EAP is a simple, but extensible protocol that was initially used by access routers to authenticate the users connected through dial-up lines. Several authentication methods, starting from the simple username/password pairs to more complex schemes have been defined and implemented. When ISPs started to upgrade their physical infrastructure to provide Internet access over Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Lines (ADSL), they tried to reuse their existing authentication (and billing) systems. To meet these requirements, the IETF developed specifications to allow PPP frames to be transported over other networks than the point-to-point links for which PPP was designed. Nowadays, most ADSL deployments use PPP over either ATM RFC 2364 or Ethernet RFC 2516.

Footnotes

- 1

- 2

The IANA maintains the registry of all assigned PPP protocol fields at : http://www.iana.org/assignments/ppp-numbers

Ethernet¶

Ethernet was designed in the 1970s at the Palo Alto Research Center [Metcalfe1976]. The first prototype 3 used a coaxial cable as the shared medium and 3 Mbps of bandwidth. Ethernet was improved during the late 1970s and in the 1980s, Digital Equipment, Intel and Xerox published the first official Ethernet specification [DIX]. This specification defines several important parameters for Ethernet networks. The first decision was to standardize the commercial Ethernet at 10 Mbps. The second decision was the duration of the slot time. In Ethernet, a long slot time enables networks to span a long distance but forces the host to use a larger minimum frame size. The compromise was a slot time of 51.2 microseconds, which corresponds to a minimum frame size of 64 bytes.

The third decision was the frame format. The experimental 3 Mbps Ethernet network built at Xerox used short frames containing 8 bit source and destination addresses fields, a 16 bit type indication, up to 554 bytes of payload and a 16 bit CRC. Using 8 bit addresses was suitable for an experimental network, but it was clearly too small for commercial deployments. Although the initial Ethernet specification [DIX] only allowed up to 1024 hosts on an Ethernet network, it also recommended three important changes compared to the networking technologies that were available at that time. The first change was to require each host attached to an Ethernet network to have a globally unique datalink layer address. Until then, datalink layer addresses were manually configured on each host. [DP1981] went against that state of the art and noted “Suitable installation-specific administrative procedures are also needed for assigning numbers to hosts on a network. If a host is moved from one network to another it may be necessary to change its host number if its former number is in use on the new network. This is easier said than done, as each network must have an administrator who must record the continuously changing state of the system (often on a piece of paper tacked to the wall !). It is anticipated that in future office environments, hosts locations will change as often as telephones are changed in present-day offices.” The second change introduced by Ethernet was to encode each address as a 48 bits field [DP1981]. 48 bit addresses were huge compared to the networking technologies available in the 1980s, but the huge address space had several advantages [DP1981] including the ability to allocate large blocks of addresses to manufacturers. Eventually, other LAN technologies opted for 48 bits addresses as well [IEEE802] . The third change introduced by Ethernet was the definition of broadcast and multicast addresses. The need for multicast Ethernet was foreseen in [DP1981] and thanks to the size of the addressing space it was possible to reserve a large block of multicast addresses for each manufacturer.

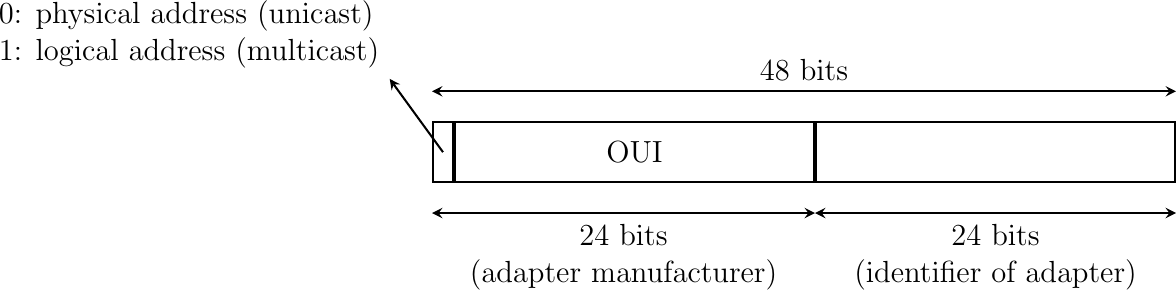

The datalink layer addresses used in Ethernet networks are often called MAC addresses. They are structured as shown in the figure below. The first bit of the address indicates whether the address identifies a network adapter or a multicast group. The upper 24 bits are used to encode an Organization Unique Identifier (OUI). This OUI identifies a block of addresses that has been allocated by the secretariat 4 that is responsible for the uniqueness of Ethernet addresses to a manufacturer. Once a manufacturer has received an OUI, it can build and sell products with one of the 16 million addresses in this block.

48 bits Ethernet address format

The original 10 Mbps Ethernet specification [DIX] defined a simple frame format where each frame is composed of five fields. The Ethernet frame starts with a preamble (not shown in the figure below) that is used by the physical layer of the receiver to synchronize its clock with the sender’s clock. The first field of the frame is the destination address. As this address is placed at the beginning of the frame, an Ethernet interface can quickly verify whether it is the frame recipient and if not, cancel the processing of the arriving frame. The second field is the source address. While the destination address can be either a unicast or a multicast/broadcast address, the source address must always be a unicast address. The third field is a 16 bits integer that indicates which type of network layer packet is carried inside the frame. This field is often called the EtherType. Frequently used EtherType values 5 include 0x0800 for IPv4, 0x86DD for IPv6 6 and 0x806 for the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP).

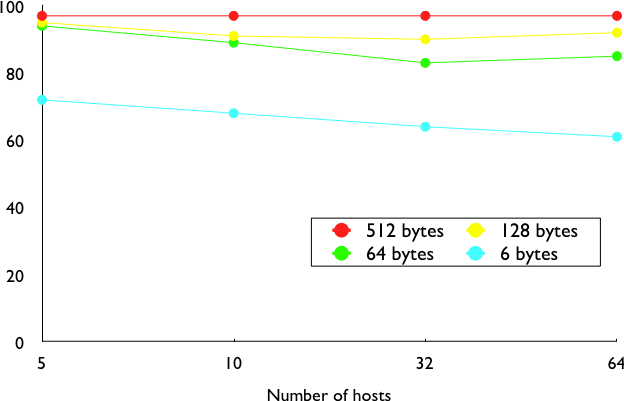

The fourth part of the Ethernet frame is the payload. The minimum length of the payload is 46 bytes to ensure a minimum frame size, including the header of 512 bits. The Ethernet payload cannot be longer than 1500 bytes. This size was found reasonable when the first Ethernet specification was written. At that time, Xerox had been using its experimental 3 Mbps Ethernet that offered 554 bytes of payload and RFC 1122 required a minimum MTU of 572 bytes for IPv4. 1500 bytes was large enough to support these needs without forcing the network adapters to contain overly large memories. Furthermore, simulations and measurement studies performed in Ethernet networks revealed that CSMA/CD was able to achieve a very high utilization. This is illustrated in the figure below based on [SH1980], which shows the channel utilization achieved in Ethernet networks containing different numbers of hosts that are sending frames of different sizes.

Impact of the frame length on the maximum channel utilization [SH1980]¶

The last field of the Ethernet frame is a 32 bit Cyclical Redundancy Check (CRC). This CRC is able to catch a much larger number of transmission errors than the Internet checksum used by IP, UDP and TCP [SGP98]. The format of the Ethernet frame is shown below.

Ethernet DIX frame format¶

Note

Where should the CRC be located in a frame ?

The transport and datalink layers usually chose different strategies to place their CRCs or checksums. Transport layer protocols usually place their CRCs or checksums in the segment header. Datalink layer protocols sometimes place their CRC in the frame header, but often in a trailer at the end of the frame. This choice reflects implementation assumptions, but also influences performance RFC 893. When the CRC is placed in the trailer, as in Ethernet, the datalink layer can compute it while transmitting the frame and insert it at the end of the transmission. All Ethernet interfaces use this optimization today. When the checksum is placed in the header, as in a TCP segment, it is impossible for the network interface to compute it while transmitting the segment. Some network interfaces provide hardware assistance to compute the TCP checksum, but this is more complex than if the TCP checksum were placed in the trailer 7.

The Ethernet frame format shown above is specified in [DIX]. This is the format used to send both IPv4 RFC 894 and IPv6 packets RFC 2464. After the publication of [DIX], the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) began to standardize several Local Area Network technologies. IEEE worked on several LAN technologies, starting with Ethernet, Token Ring and Token Bus. These three technologies were completely different, but they all agreed to use the 48 bits MAC addresses specified initially for Ethernet [IEEE802] . While developing its Ethernet standard [IEEE802.3], the IEEE 802.3 working group was confronted with a problem. Ethernet mandated a minimum payload size of 46 bytes, while some companies were looking for a LAN technology that could transparently transport short frames containing only a few bytes of payload. Such a frame can be sent by an Ethernet host by padding it to ensure that the payload is at least 46 bytes long. However since the Ethernet header [DIX] does not contain a length field, it is impossible for the receiver to determine how many useful bytes were placed inside the payload field. To solve this problem, the IEEE decided to replace the Type field of the Ethernet [DIX] header with a length field 8. This Length field contains the number of useful bytes in the frame payload. The payload must still contain at least 46 bytes, but padding bytes are added by the sender and removed by the receiver. In order to add the Length field without significantly changing the frame format, IEEE had to remove the Type field. Without this field, it is impossible for a receiving host to identify the type of network layer packet inside a received frame. To solve this new problem, IEEE developed a completely new sublayer called the Logical Link Control [IEEE802.2]. Several protocols were defined in this sublayer. One of them provided a slightly different version of the Type field of the original Ethernet frame format. Another contained acknowledgments and retransmissions to provide a reliable service… In practice, [IEEE802.2] is never used to support IP in Ethernet networks. The figure below shows the official [IEEE802.3] frame format.

Ethernet 802.3 frame format¶

Note

What is the Ethernet service ?

An Ethernet network provides an unreliable connectionless service. It supports three different transmission modes : unicast, multicast and broadcast. While the Ethernet service is unreliable in theory, a good Ethernet network should, in practice, provide a service that:

delivers frames to their destination with a very high probability of successful delivery

does not reorder the transmitted frames

The first property is a consequence of the utilization of CSMA/CD. The second property is a consequence of the physical organization of the Ethernet network as a shared bus. These two properties are important and all revisions to the Ethernet technology have preserved them.

Several physical layers have been defined for Ethernet networks. The first physical layer, usually called 10Base5, provided 10 Mbps over a thick coaxial cable. The characteristics of the cable and the transceivers that were used then enabled the utilization of 500 meter long segments. A 10Base5 network can also include repeaters between segments.

The second physical layer was 10Base2. This physical layer used a thin coaxial cable that was easier to install than the 10Base5 cable, but could not be longer than 185 meters. A 10BaseF physical layer was also defined to transport Ethernet over point-to-point optical links. The major change to the physical layer was the support of twisted pairs in the 10BaseT specification. Twisted pair cables are traditionally used to support the telephone service in office buildings. Most office buildings today are equipped with structured cabling. Several twisted pair cables are installed between any room and a central telecom closet per building or per floor in large buildings. These telecom closets act as concentration points for the telephone service but also for LANs.

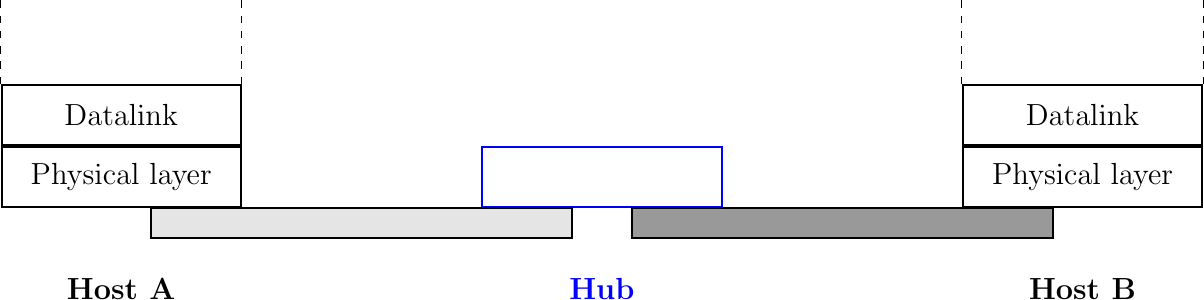

The introduction of the twisted pairs led to two major changes to Ethernet. The first change concerns the physical topology of the network. 10Base2 and 10Base5 networks are shared buses, the coaxial cable typically passes through each room that contains a connected computer. A 10BaseT network is a star-shaped network. All the devices connected to the network are attached to a twisted pair cable that ends in the telecom closet. From a maintenance perspective, this is a major improvement. The cable is a weak point in 10Base2 and 10Base5 networks. Any physical damage on the cable broke the entire network and when such a failure occurred, the network administrator had to manually check the entire cable to detect where it was damaged. With 10BaseT, when one twisted pair is damaged, only the device connected to this twisted pair is affected and this does not affect the other devices. The second major change introduced by 10BaseT was that is was impossible to build a 10BaseT network by simply connecting all the twisted pairs together. All the twisted pairs must be connected to a relay that operates in the physical layer. This relay is called an Ethernet hub. A hub is thus a physical layer relay that receives an electrical signal on one of its interfaces, regenerates the signal and transmits it over all its other interfaces. Some hubs are also able to convert the electrical signal from one physical layer to another (e.g. 10BaseT to 10Base2 conversion).

Ethernet hubs in the reference model

Computers can directly be attached to Ethernet hubs. Ethernet hubs themselves can be attached to other Ethernet hubs to build a larger network. However, some important guidelines must be followed when building a complex network with hubs. First, the network topology must be a tree. As hubs are relays in the physical layer, adding a link between Hub2 and Hub3 in the network below would create an electrical shortcut that would completely disrupt the network. This implies that there cannot be any redundancy in a hub-based network. A failure of a hub or of a link between two hubs would partition the network into two isolated networks. Second, as hubs are relays in the physical layer, collisions can happen and must be handled by CSMA/CD as in a 10Base5 network. This implies that the maximum delay between any pair of devices in the network cannot be longer than the 51.2 microseconds slot time. If the delay is longer, collisions between short frames may not be correctly detected. This constraint limits the geographical spread of 10BaseT networks containing hubs.

A hierarchical Ethernet network composed of hubs¶

In the late 1980s, 10 Mbps became too slow for some applications and network manufacturers developed several LAN technologies that offered higher bandwidth, such as the 100 Mbps FDDI LAN that used optical fibers. As the development of 10Base5, 10Base2 and 10BaseT had shown that Ethernet could be adapted to different physical layers, several manufacturers started to work on 100 Mbps Ethernet and convinced IEEE to standardize this new technology that was initially called Fast Ethernet. Fast Ethernet was designed under two constraints. First, Fast Ethernet had to support twisted pairs. Although it was easier from a physical layer perspective to support higher bandwidth on coaxial cables than on twisted pairs, coaxial cables were a nightmare from deployment and maintenance perspectives. Second, Fast Ethernet had to be perfectly compatible with the existing 10 Mbps Ethernet to allow Fast Ethernet technology to be used initially as a backbone technology to interconnect 10 Mbps Ethernet networks. This forced Fast Ethernet to use exactly the same frame format as 10 Mbps Ethernet. This implied that the minimum Fast Ethernet frame size remained at 512 bits. To preserve CSMA/CD with this minimum frame size and 100 Mbps instead of 10 Mbps, the duration of the slot time was decreased to 5.12 microseconds.

The evolution of Ethernet did not stop. In 1998, the IEEE published a first standard to provide Gigabit Ethernet over optical fibers. Several other types of physical layers were added afterwards. The 10 Gigabit Ethernet standard appeared in 2002. Work is ongoing to develop standards for 40 Gigabit and 100 Gigabit Ethernet and some are thinking about Terabit Ethernet. The table below lists the main Ethernet standards. A more detailed list may be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethernet_physical_layer.

Standard |

Comments |

|---|---|

10Base5 |

Thick coaxial cable, 500m |

10Base2 |

Thin coaxial cable, 185m |

10BaseT |

Two pairs of category 3+ UTP |

10Base-F |

10 Mb/s over optical fiber |

100Base-Tx |

Category 5 UTP or STP, 100 m maximum |

100Base-FX |

Two multi-mode optical fiber, 2 km maximum |

1000Base-CX |

Two pairs shielded twisted pair, 25m maximum |

1000Base-SX |

Two multi-mode or single mode optical fibers with lasers |

10 Gbps |

Optical fiber but also Category 6 UTP |

40-100 Gbps |

Optical fiber (experiences are performed with copper) |

Footnotes

- 3

Additional information about the history of the Ethernet technology may be found at http://ethernethistory.typepad.com/

- 4

Initially, the OUIs were allocated by Xerox [DP1981]. However, once Ethernet became an IEEE and later an ISO standard, the allocation of the OUIs moved to IEEE. The list of all OUI allocations may be found at http://standards.ieee.org/regauth/oui/index.shtml

- 5

The official list of all assigned Ethernet type values is available from http://standards.ieee.org/regauth/ethertype/eth.txt

- 6

The attentive reader may question the need for different EtherTypes for IPv4 and IPv6 while the IP header already contains a version field that can be used to distinguish between IPv4 and IPv6 packets. Theoretically, IPv4 and IPv6 could have used the same EtherType. Unfortunately, developers of the early IPv6 implementations found that some devices did not check the version field of the IPv4 packets that they received and parsed frames whose EtherType was set to 0x0800 as IPv4 packets. Sending IPv6 packets to such devices would have caused disruptions. To avoid this problem, the IETF decided to apply for a distinct EtherType value for IPv6. Such a choice is now mandated by RFC 6274 (section 3.1), although we can find a funny counter-example in RFC 6214.

- 7

These network interfaces compute the TCP checksum while a segment is transferred from the host memory to the network interface [SH2004].

- 8

Fortunately, IEEE was able to define the [IEEE802.3] frame format while maintaining backward compatibility with the Ethernet [DIX] frame format. The trick was to only assign values above 1500 as EtherType values. When a host receives a frame, it can determine whether the frame’s format by checking its EtherType/Length field. A value lower smaller than 1501 is clearly a length indicator and thus an [IEEE802.3] frame. A value larger than 1501 can only be type and thus a [DIX] frame.

Ethernet Switches¶

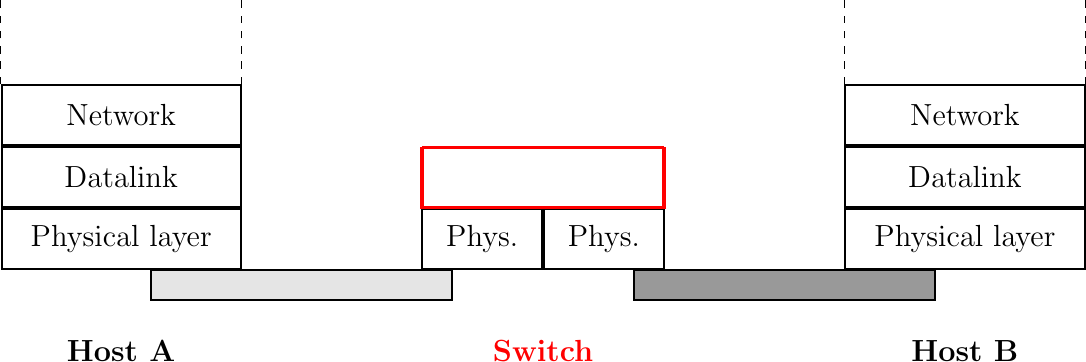

Increasing the physical layer bandwidth as in Fast Ethernet was only one of the solutions to improve the performance of Ethernet LANs. A second solution was to replace the hubs with more intelligent devices. As Ethernet hubs operate in the physical layer, they can only regenerate the electrical signal to extend the geographical reach of the network. From a performance perspective, it would be more interesting to have devices that operate in the datalink layer and can analyze the destination address of each frame and forward the frames selectively on the link that leads to the destination. Such devices are usually called Ethernet switches 9. An Ethernet switch is a relay that operates in the datalink layer as is illustrated in the figure below.

Ethernet switches in the reference model

An Ethernet switch understands the format of the Ethernet frames and can selectively forward frames over each interface. For this, each Ethernet switch maintains a MAC address table. This table contains, for each MAC address known by the switch, the identifier of the switch’s port over which a frame sent towards this address must be forwarded to reach its destination. This is illustrated below with the MAC address table of the bottom switch. When the switch receives a frame destined to address B, it forwards the frame on its South port. If it receives a frame destined to address D, it forwards it only on its North port.

Operation of Ethernet switches¶

One of the selling points of Ethernet networks is that, thanks to the utilization of 48 bits MAC addresses, an Ethernet LAN is plug and play at the datalink layer. When two hosts are attached to the same Ethernet segment or hub, they can immediately exchange Ethernet frames without requiring any configuration. It is important to retain this plug and play capability for Ethernet switches as well. This implies that Ethernet switches must be able to build their MAC address table automatically without requiring any manual configuration. This automatic configuration is performed by the MAC address learning algorithm that runs on each Ethernet switch. This algorithm extracts the source address of the received frames and remembers the port over which a frame from each source Ethernet address has been received. This information is inserted into the MAC address table that the switch uses to forward frames. This allows the switch to automatically learn the ports that it can use to reach each destination address, provided that this host has previously sent at least one frame. This is not a problem since most upper layer protocols use acknowledgments at some layer and thus even an Ethernet printer sends Ethernet frames as well.

The pseudo-code below details how an Ethernet switch forwards Ethernet frames. It first updates its MAC address table with the source address of the frame. The MAC address table used by some switches also contains a timestamp that is updated each time a frame is received from each known source address. This timestamp is used to remove from the MAC address table entries that have not been active during the last n minutes. This limits the growth of the MAC address table, but also allows hosts to move from one port to another. The switch uses its MAC address table to forward the received unicast frame. If there is an entry for the frame’s destination address in the MAC address table, the frame is forwarded selectively on the port listed in this entry. Otherwise, the switch does not know how to reach the destination address and it must forward the frame on all its ports except the port from which the frame has been received. This ensures that the frame will reach its destination, at the expense of some unnecessary transmissions. These unnecessary transmissions will only last until the destination has sent its first frame. Multicast and Broadcast frames are also forwarded in a similar way.

# Arrival of frame F on port P

# Table : MAC address table dictionary : addr->port

# Ports : list of all ports on the switch

src = F.SourceAddress

dst = F.DestinationAddress

Table[src] = P # src heard on port P

if is_unicast(dst):

if dst in Table:

forward_frame(F, Table[dst])

else:

for o in Ports:

if o != P:

forward_frame(F, o)

else:

# multicast or broadcast destination

for o in Ports:

if o != P:

forward_frame(F, o)

Note

Security issues with Ethernet hubs and switches

From a security perspective, Ethernet hubs have the same drawbacks as the older coaxial cable. A host attached to a hub will be able to capture all the frames exchanged between any pair of hosts attached to the same hub. Ethernet switches are much better from this perspective thanks to the selective forwarding, a host will usually only receive the frames destined to itself as well as the multicast, broadcast and unknown frames. However, this does not imply that switches are completely secure. There are, unfortunately, attacks against Ethernet switches. From a security perspective, the MAC address table is one of the fragile elements of an Ethernet switch. This table has a fixed size. Some low-end switches can store a few tens or a few hundreds of addresses while higher-end switches can store tens of thousands of addresses or more. From a security point of view, a limited resource can be the target of Denial of Service attacks. Unfortunately, such attacks are also possible on Ethernet switches. A malicious host could overflow the MAC address table of the switch by generating thousands of frames with random source addresses. Once the MAC address table is full, the switch needs to broadcast all the frames that it receives. At this point, an attacker will receive unicast frames that are not destined to its address. The ARP attack discussed in the previous chapter could also occur with Ethernet switches [Vyncke2007]. Recent switches implement several types of defenses against these attacks, but they need to be carefully configured by the network administrator. See [Vyncke2007] for a detailed discussion on security issues with Ethernet switches.

The MAC address learning algorithm combined with the forwarding algorithm work well in a tree-shaped network such as the one shown above. However, to deal with link and switch failures, network administrators often add redundant links to ensure that their network remains connected even after a failure. Let us consider what happens in the Ethernet network shown in the figure below.

Ethernet switches in a loop¶

When all switches boot, their MAC address table is empty. Assume that host A sends a frame towards host C. Upon reception of this frame, switch1 updates its MAC address table to remember that address A is reachable via its West port. As there is no entry for address C in switch1’s MAC address table, the frame is forwarded to both switch2 and switch3. When switch2 receives the frame, its updates its MAC address table for address A and forwards the frame to host C as well as to switch3. switch3 has thus received two copies of the same frame. As switch3 does not know how to reach the destination address, it forwards the frame received from switch1 to switch2 and the frame received from switch2 to switch1… The single frame sent by host A will be continuously duplicated by the switches until their MAC address table contains an entry for address C. Quickly, all the available link bandwidth will be used to forward all the copies of this frame. As Ethernet does not contain any TTL or HopLimit, this loop will never stop.

The MAC address learning algorithm allows switches to be plug-and-play. Unfortunately, the loops that arise when the network topology is not a tree are a severe problem. Forcing the switches to only be used in tree-shaped networks as hubs would be a severe limitation. To solve this problem, the inventors of Ethernet switches have developed the Spanning Tree Protocol. This protocol allows switches to automatically disable ports on Ethernet switches to ensure that the network does not contain any cycle that could cause frames to loop forever.

Footnotes

- 9

The first Ethernet relays that operated in the datalink layers were called bridges. In practice, the main difference between switches and bridges is that bridges were usually implemented in software while switches are hardware-based devices. Throughout this text, we always use switch when referring to a relay in the datalink layer, but you might still see the word bridge.

The Spanning Tree Protocol (802.1d)¶

The Spanning Tree Protocol (STP), proposed in [Perlman1985], is a distributed protocol that is used by switches to reduce the network topology to a spanning tree, so that there are no cycles in the topology. For example, consider the network shown in the figure below. In this figure, each bold line corresponds to an Ethernet to which two Ethernet switches are attached. This network contains several cycles that must be broken to allow Ethernet switches, using the MAC address learning algorithm, to exchange frames.

Spanning tree computed in a switched Ethernet network¶

In this network, the STP will compute the following spanning tree. Switch1 will be the root of the tree. All the interfaces of Switch1, Switch2 and Switch7 are part of the spanning tree. Only the interface connected to LAN B will be active on Switch9. LAN H will only be served by Switch7 and the port of Switch44 on LAN G will be disabled. A frame originating on LAN B and destined for LAN A will be forwarded by Switch7 on LAN C, then by Switch1 on LAN E, then by Switch44 on LAN F and eventually by Switch2 on LAN A.

Switches running the Spanning Tree Protocol exchange BPDUs. These BPDUs are always sent as frames with destination MAC address as the ALL_BRIDGES reserved multicast MAC address. Each switch has a unique 64 bit identifier. To ensure uniqueness, the lower 48 bits of the identifier are set to the unique MAC address allocated to the switch by its manufacturer. The high order 16 bits of the switch identifier can be configured by the network administrator to influence the topology of the spanning tree. The default value for these high order bits is 32768.

The switches exchange BPDUs to build the spanning tree. Intuitively, the spanning tree is built by first selecting the switch with the smallest identifier as the root of the tree. The branches of the spanning tree are then composed of the shortest paths that allow all of the switches that compose the network to be reached. The BPDUs exchanged by the switches contain the following information :

the identifier of the root switch (R)

the cost of the shortest path between the switch that sent the BPDU and the root switch (c)

the identifier of the switch that sent the BPDU (T)

the number of the switch port over which the BPDU was sent (p)

We will use the notation <R,c,T,p> to represent a BPDU whose root identifier is R, cost is c and that was sent from the port p of switch T. The construction of the spanning tree depends on an ordering relationship among the BPDUs. This ordering relationship could be implemented by the Python function below.

# returns True if bpdu b1 is better than bpdu b2

def better(b1, b2):

return ((b1.R < b2.R) or

((b1.R == b2.R) and (b1.c < b2.c)) or

((b1.R == b2.R) and (b1.c == b2.c) and (b1.T < b2.T)) or

((b1.R == b2.R) and (b1.c == b2.c) and (b1.T == b2.T) and (b1.p < b2.p)))

In addition to the identifier discussed above, the network administrator can also configure a cost to be associated to each switch port. Usually, the cost of a port depends on its bandwidth and the [IEEE802.1d] standard recommends the values below. Of course, the network administrator may choose other values. We will use the notation cost[p] to indicate the cost associated to port p in this section.

Bandwidth |

Cost |

|---|---|

10 Mbps |

2000000 |

100 Mbps |

200000 |

1 Gbps |

20000 |

10 Gbps |

2000 |

100 Gbps |

200 |

The Spanning Tree Protocol uses its own terminology that we illustrate in the figure above. A switch port can be in three different states : Root, Designated and Blocked. All the ports of the root switch are in the Designated state. The state of the ports on the other switches is determined based on the BPDU received on each port.

The Spanning Tree Protocol uses the ordering relationship to build the spanning tree. Each switch listens to BPDUs on its ports. When BPDU = <R,c,T,p> is received on port q, the switch computes the port’s root priority vector: V[q] = <R,c+cost[q],T,p,q> , where cost[q] is the cost associated to the port over which the BPDU was received. The switch stores in a table the last root priority vector received on each port. The switch then compares its own identifier with the smallest root identifier stored in this table. If its own identifier is smaller, then the switch is the root of the spanning tree and is, by definition, at a distance 0 of the root. The BPDU of the switch is then <R,0,R,p>, where R is the switch identifier and p will be set to the port number over which the BPDU is sent.

Otherwise, the switch chooses the best priority vector from its table, bv = <R,c+cost[q’],T,p,q’>. The port q’, over which this best root priority vector was learned, is the switch port that is closest to the root switch. This port becomes the Root port of the switch. There is only one Root port per switch (except for the Root switches whose ports are all Designated). The switch can then compute its own BPDU as BPDU = <R,c’,S,p> , where R is the root identifier, c’ the cost of the best root priority vector, S the identifier of the switch and p will be replaced by the number of the port over which the BPDU will be sent.

To determine the state of its other ports, the switch compares its own BPDU with the last BPDU received on each port. Note that the comparison is done by using the BPDUs and not the root priority vectors. If the switch’s BPDU is better than the last BPDU of this port, the port becomes a Designated port. Otherwise, the port becomes a Blocked port.

The state of each port is important when considering the transmission of BPDUs. The root switch regularly sends its own BPDU over all of its (Designated) ports. This BPDU is received on the Root port of all the switches that are directly connected to the root switch. Each of these switches computes its own BPDU and sends this BPDU over all its Designated ports. These BPDUs are then received on the Root port of downstream switches, which then compute their own BPDU, etc. When the network topology is stable, switches send their own BPDU on all their Designated ports, once they receive a BPDU on their Root port. No BPDU is sent on a Blocked port. Switches listen for BPDUs on their Blocked and Designated ports, but no BPDU should be received over these ports when the topology is stable. The utilization of the ports for both BPDUs and data frames is summarized in the table below.

Port state |

Receives BPDUs |

Sends BPDU |

Handles data frames |

|---|---|---|---|

Blocked |

yes |

no |

no |

Root |

yes |

no |

yes |

Designated |

yes |

yes |

yes |

To illustrate the operation of the Spanning Tree Protocol, let us consider the simple network topology in the figure below.

A simple Spanning tree computed in a switched Ethernet network¶

Assume that Switch4 is the first to boot. It sends its own BPDU = <4,0,4,1> (resp. BPDU = <4,0,4,2>) on port 1 (resp. port 2). When Switch1 boots, it sends BPDU = <1,0,1,1>. This BPDU is received by Switch4, which updates its BPDU and root priority vector tables and computes a new BPDU = <1,3,4,1> (resp. BPDU = <1,3,4,2>) on port 1 (resp. port 2). Indeed, there is only one root priority vector and hence, it is the best one. Port 1 of Switch4 becomes the Root port while its second port is still in the Designated state.

Assume now that Switch9 boots and immediately receives Switch1 ‘s BPDU on port 1. Switch9 computes its own BPDU = <1,1,9,1> (resp. BPDU = <1,1,9,2>) on port 1 (resp. port 2) and port 1 becomes the Root port of this switch. The BPDU is sent on port 2 of Switch9 and reaches Switch4. Switch4 compares the priority vectors. It notices that the last computed vector (i.e., V[2] = <1,2,9,2,2>) is better than V[1] = <1,3,1,1,1>. Thus, Switch4’s BPDU is recomputed and port 2 becomes the Root port of Switch4. Switch4 compares its new BPDU = <1,2,4,p> with the last BPDU received on each port (except for the Root port). Port 1 becomes a Blocked port on Switch4 because the BPDU=<1,0,1,1> received on this port is better.

During the computation of the spanning tree, switches discard all received data frames, as at that time the network topology is not guaranteed to be loop-free. Once that topology has been stable for some time, the switches again start to use the MAC learning algorithm to forward data frames. Only the Root and Designated ports are used to forward data frames. Switches discard all the data frames received on their Blocked ports and never forward frames on these ports.

Switches, ports and links can fail in a switched Ethernet network. When a failure occurs, the switches must be able to recompute the spanning tree to recover from the failure. The Spanning Tree Protocol relies on regular transmissions of the BPDUs to detect these failures. A BPDU contains two additional fields : the Age of the BPDU and the Maximum Age. The Age contains the amount of time that has passed since the root switch initially originated the BPDU. The root switch sends its BPDU with an Age of zero and each switch that computes its own BPDU increments its Age by one. The Age of the BPDUs stored on a switch’s table is also incremented every second. A BPDU expires when its Age reaches the Maximum Age. When the network is stable, this does not happen as BPDU s are regularly sent by the root switch and downstream switches. However, if the root fails or the network becomes partitioned, BPDU will expire and switches will recompute their own BPDU and restart the Spanning Tree Protocol. Once a topology change has been detected, the forwarding of the data frames stops as the topology is not guaranteed to be loop-free. Additional details about the reaction to failures may be found in [IEEE802.1d].

Virtual LANs¶

Another important advantage of Ethernet switches is the ability to create Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs). A virtual LAN can be defined as a set of ports attached to one or more Ethernet switches. A switch can support several VLANs and it runs one MAC learning algorithm for each Virtual LAN. When a switch receives a frame with an unknown or a multicast destination, it forwards it over all the ports that belong to the same Virtual LAN but not over the ports that belong to other Virtual LANs. Similarly, when a switch learns a source address on a port, it associates it to the Virtual LAN of this port and uses this information only when forwarding frames on this Virtual LAN.

The figure below illustrates a switched Ethernet network with three Virtual LANs. VLAN2 and VLAN3 only require a local configuration of switch S1. Host C can exchange frames with host D, but not with hosts that are outside of its VLAN. VLAN1 is more complex as there are ports of this VLAN on several switches. To support such VLANs, local configuration is not sufficient anymore. When a switch receives a frame from another switch, it must be able to determine the VLAN in which the frame originated to use the correct MAC table to forward the frame. This is done by assigning an identifier to each Virtual LAN and placing this identifier inside the headers of the frames that are exchanged between switches.

Virtual Local Area Networks in a switched Ethernet network¶

IEEE defined in the [IEEE802.1q] standard a special header to encode the VLAN identifiers. This 32 bit header includes a 12 bit VLAN field that contains the VLAN identifier of each frame. The format of the [IEEE802.1q] header is described below.

Format of the 802.1q header¶

The [IEEE802.1q] header is inserted immediately after the source MAC address in the Ethernet frame (i.e. before the EtherType field). The maximum frame size is increased by 4 bytes. It is encoded in 32 bits and contains four fields. The Tag Protocol Identifier is set to 0x8100 to allow the receiver to detect the presence of this additional header. The Priority Code Point (PCP) is a three bit field that is used to support different transmission priorities for the frame. Value 0 is the lowest priority and value 7 the highest. Frames with a higher priority can expect to be forwarded earlier than frames having a lower priority. The C bit is used for compatibility between Ethernet and Token Ring networks. The last 12 bits of the 802.1q header contain the VLAN identifier. Value 0 indicates that the frame does not belong to any VLAN while value 0xFFF is reserved. This implies that 4094 different VLAN identifiers can be used in an Ethernet network.

802.11 wireless networks¶

The radio spectrum is a limited resource that must be shared by everyone. During most of the twentieth century, governments and international organizations have regulated most of the radio spectrum. This regulation controls the utilization of the radio spectrum, in order to prevent interference among different users. A company that wants to use a frequency range in a given region must apply for a license from the regulator. Most regulators charge a fee for the utilization of the radio spectrum and some governments have encouraged competition among companies bidding for the same frequency to increase the license fees.

In the 1970s, after the first experiments with ALOHANet, interest in wireless networks grew. Many experiments were done on and outside the ARPANet. One of these experiments was the first mobile phone , which was developed and tested in 1973. This experimental mobile phone was the starting point for the first generation analog mobile phones. Given the growing demand for mobile phones, it was clear that the analog mobile phone technology was not sufficient to support a large number of users. To support more users and new services, researchers in several countries worked on the development of digital mobile telephones. In 1987, several European countries decided to develop the standards for a common cellular telephone system across Europe : the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM). Since then, the standards have evolved and more than three billion users are connected to GSM networks today.

While most of the frequency ranges of the radio spectrum are reserved for specific applications and require a special license, there are a few exceptions. These exceptions are known as the Industrial, Scientific and Medical (ISM) radio bands. These bands can be used for industrial, scientific and medical applications without requiring a license from the regulator. For example, some radio-controlled models use the 27 MHz ISM band and some cordless telephones operate in the 915 MHz ISM. In 1985, the 2.400-2.500 GHz band was added to the list of ISM bands. This frequency range corresponds to the frequencies that are emitted by microwave ovens. Sharing this band with licensed applications would have likely caused interference, given the large number of microwave ovens that are used. Despite the risk of interference with microwave ovens, the opening of the 2.400-2.500 GHz allowed the networking industry to develop several wireless network techniques to allow computers to exchange data without using cables. In this section, we discuss in more detail the most popular one, i.e. the WiFi [IEEE802.11] family of wireless networks. Other wireless networking techniques such as BlueTooth or HiperLAN use the same frequency range.

Today, WiFi is a very popular wireless networking technology. There are more than several hundreds of millions of WiFi devices. The development of this technology started in the late 1980s with the WaveLAN proprietary wireless network. WaveLAN operated at 2 Mbps and used different frequency bands in different regions of the world. In the early 1990s, the IEEE created the 802.11 working group to standardize a family of wireless network technologies. This working group was very prolific and produced several wireless networking standards that use different frequency ranges and different physical layers. The table below provides a summary of the main 802.11 standards.

Standard |

Frequency |

Typical throughput |

Max bandwidth |

Range (m) indoor/outdoor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

802.11 |

2.4 GHz |

0.9 Mbps |

2 Mbps |

20/100 |

802.11a |

5 GHz |

23 Mbps |

54 Mbps |

35/120 |

802.11b |

2.4 GHz |

4.3 Mbps |

11 Mbps |

38/140 |

802.11g |

2.4 GHz |

19 Mbps |

54 Mbps |

38/140 |

802.11n |

2.4/5 GHz |

74 Mbps |

150 Mbps |

70/250 |

When developing its family of standards, the IEEE 802.11 working group took a similar approach as the IEEE 802.3 working group that developed various types of physical layers for Ethernet networks. 802.11 networks use the CSMA/CA Medium Access Control technique described earlier and they all assume the same architecture and use the same frame format.

The architecture of WiFi networks is slightly different from the Local Area Networks that we have discussed until now. There are, in practice, two main types of WiFi networks : independent or adhoc networks and infrastructure networks 10. An independent or adhoc network is composed of a set of devices that communicate with each other. These devices play the same role and the adhoc network is usually not connected to the global Internet. Adhoc networks are used when for example a few laptops need to exchange information or to connect a computer with a WiFi printer.

An 802.11 independent or adhoc network¶

Most WiFi networks are infrastructure networks. An infrastructure network contains one or more access points that are attached to a fixed Local Area Network (usually an Ethernet network) that is connected to other networks such as the Internet. The figure below shows such a network with two access points and four WiFi devices. Each WiFi device is associated to one access point and uses this access point as a relay to exchange frames with the devices that are associated to another access point or reachable through the LAN.

An 802.11 infrastructure network¶

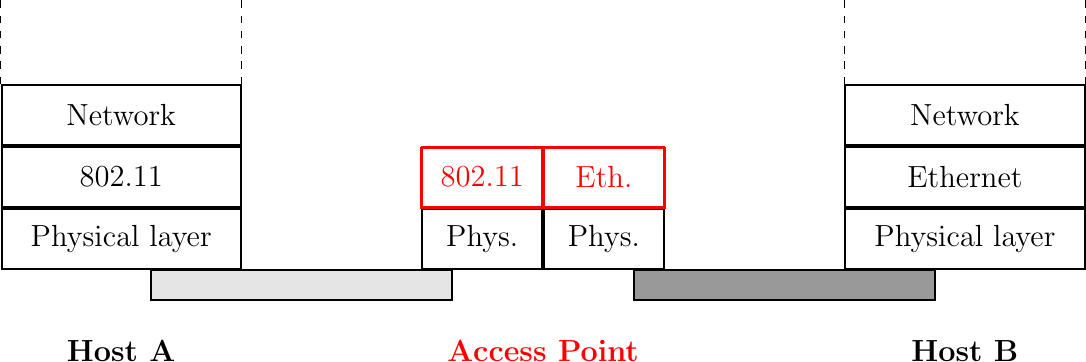

An 802.11 access point is a relay that operates in the datalink layer like switches. The figure below represents the layers of the reference model that are involved when a WiFi host communicates with a host attached to an Ethernet network through an access point.

An 802.11 access point

802.11 devices exchange variable length frames, which have a slightly different structure than the simple frame format used in Ethernet LANs. We review the key parts of the 802.11 frames. Additional details may be found in [IEEE802.11] and [Gast2002] . An 802.11 frame contains a fixed length header, a variable length payload that may contain up 2324 bytes of user data and a 32 bits CRC. Although the payload can contain up to 2324 bytes, most 802.11 deployments use a maximum payload size of 1500 bytes as they are used in infrastructure networks attached to Ethernet LANs. An 802.11 data frame is shown below.

802.11 data frame format¶

The first part of the 802.11 header is the 16 bit Frame Control field. This field contains flags that indicate the type of frame (data frame, RTS/CTS, acknowledgment, management frames, etc), whether the frame is sent to or from a fixed LAN, etc [IEEE802.11]. The Duration is a 16 bit field that is used to reserve the transmission channel. In data frames, the Duration field is usually set to the time required to transmit one acknowledgment frame after a SIFS delay. Note that the Duration field must be set to zero in multicast and broadcast frames. As these frames are not acknowledged, there is no need to reserve the transmission channel after their transmission. The Sequence control field contains a 12 bits sequence number that is incremented for each data frame and a 4 bits fragment number.

The astute reader may have noticed that the 802.11 data frames contain three 48-bits address fields 11 . This is surprising compared to other protocols in the network and datalink layers whose headers only contain a source and a destination address. The need for a third address in the 802.11 header comes from the infrastructure networks. In such a network, frames are usually exchanged between routers and servers attached to the LAN and WiFi devices attached to one of the access points. The role of the three address fields is specified by bit flags in the Frame Control field.

When a frame is sent from a WiFi device to a server attached to the same LAN as the access point, the first address of the frame is set to the MAC address of the access point, the second address is set to the MAC address of the source WiFi device and the third address is the address of the final destination on the LAN. When the server replies, it sends an Ethernet frame whose source address is its MAC address and the destination address is the MAC address of the WiFi device. This frame is captured by the access point that converts the Ethernet header into an 802.11 frame header. The 802.11 frame sent by the access point contains three addresses : the first address is the MAC address of the destination WiFi device, the second address is the MAC address of the access point and the third address the MAC address of the server that sent the frame.

802.11 control frames are simpler than data frames. They contain a Frame Control, a Duration field and one or two addresses. The acknowledgment frames are very small. They only contain the address of the destination of the acknowledgment. There is no source address and no Sequence Control field in the acknowledgment frames. This is because the acknowledgment frame can easily be associated to the previous frame that it acknowledges. Indeed, each unicast data frame contains a Duration field that is used to reserve the transmission channel to ensure that no collision will affect the acknowledgment frame. The Sequence Control field is mainly used by the receiver to remove duplicate frames. Duplicate frames are detected as follows. Each data frame contains a 12 bits sequence number in the Sequence Control field and the Frame Control field contains the Retry bit flag that is set when a frame is transmitted. Each 802.11 receiver stores the most recent sequence number received from each source address in frames whose Retry bit is reset. Upon reception of a frame with the Retry bit set, the receiver verifies its sequence number to determine whether it is a duplicated frame or not.

IEEE 802.11 ACK and CTS frames¶

802.11 RTS/CTS frames are used to reserve the transmission channel, in order to transmit one data frame and its acknowledgment. The RTS frames contain a Duration and the transmitter and receiver addresses. The Duration field of the RTS frame indicates the duration of the entire reservation (i.e. the time required to transmit the CTS, the data frame, the acknowledgments and the required SIFS delays). The CTS frame has the same format as the acknowledgment frame.

IEEE 802.11 RTS frame format¶

Note

The 802.11 service

Despite the utilization of acknowledgments, the 802.11 layer only provides an unreliable connectionless service like Ethernet networks that do not use acknowledgments. The 802.11 acknowledgments are used to minimize the probability of frame duplication. They do not guarantee that all frames will be correctly received by their recipients. Like Ethernet, 802.11 networks provide a high probability of successful delivery of the frames, not a guarantee. Furthermore, it should be noted that 802.11 networks do not use acknowledgments for multicast and broadcast frames. This implies that in practice such frames are more likely to suffer from transmission errors than unicast frames.

In addition to the data and control frames that we have briefly described above, 802.11 networks use several types of management frames. These management frames are used for various purposes. We briefly describe some of these frames below. A detailed discussion may be found in [IEEE802.11] and [Gast2002].

A first type of management frames are the beacon frames. These frames are broadcasted regularly by access points. Each beacon frame contains information about the capabilities of the access point (e.g. the supported 802.11 transmission rates) and a Service Set Identity (SSID). The SSID is a null-terminated ASCII string that can contain up to 32 characters. An access point may support several SSIDs and announce them in beacon frames. An access point may also choose to remain silent and not advertise beacon frames. In this case, WiFi stations may send Probe request frames to force the available access points to return a Probe response frame.

Note

IP over 802.11

Two types of encapsulation schemes were defined to support IP in Ethernet networks : the original encapsulation scheme, built above the Ethernet DIX format is defined in RFC 894 and a second encapsulation RFC 1042 scheme, built above the LLC/SNAP protocol [IEEE802.2]. In 802.11 networks, the situation is simpler and only the RFC 1042 encapsulation is used. In practice, this encapsulation adds 6 bytes to the 802.11 header. The first four bytes correspond to the LLC/SNAP header. They are followed by the two bytes Ethernet Type field (0x800 for IP and 0x806 for ARP). The figure below shows an IP packet encapsulated in an 802.11 frame.

IP over IEEE 802.11¶

The second important utilization of the management frames is to allow a WiFi station to be associated with an access point. When a WiFi station starts, it listens to beacon frames to find the available SSIDs. To be allowed to send and receive frames via an access point, a WiFi station must be associated to this access point. If the access point does not use any security mechanism to secure the wireless transmission, the WiFi station simply sends an Association request frame to its preferred access point (usually the access point that it receives with the strongest radio signal). This frame contains some parameters chosen by the WiFi station and the SSID that it requests to join. The access point replies with an Association response frame if it accepts the WiFI station.

Footnotes

- 10

The 802.11 working group defined the basic service set (BSS) as a group of devices that communicate with each other. We continue to use network when referring to a set of devices that communicate.

- 11

In fact, the [IEEE802.11] frame format contains a fourth optional address field. This fourth address is only used when an 802.11 wireless network is used to interconnect bridges attached to two classical LAN networks.