Making HTTP faster

Making HTTP faster¶

During the last decade, a growing number of services have been supported by world wide web servers. The web protocols are not only used to deliver static documents, they are also used to deliver streaming music or video. They also enable clients to use interactive applications including games or productivity applications. These services and applications have more stringent performance requirements than the delivery of static documents. Many researchers and companies have proposed solutions to improve the performance of web services and protocols during the last decade [KR2001] [WBK2014]. We discuss a subset of them in this section.

A first way to improve the performance of the web protocols is to tune the servers that provide content. In the early days, documents were stored on a single server. Clients established TCP connections to this server to retrieve each document. This architecture evolved in several directions. A first way to speedup web services is to avoid unnecessary transmissions. Thanks to the HEAD method and the If-Modified-Since: header, web browsers can verify that they have the most recent version of a document in their cache.

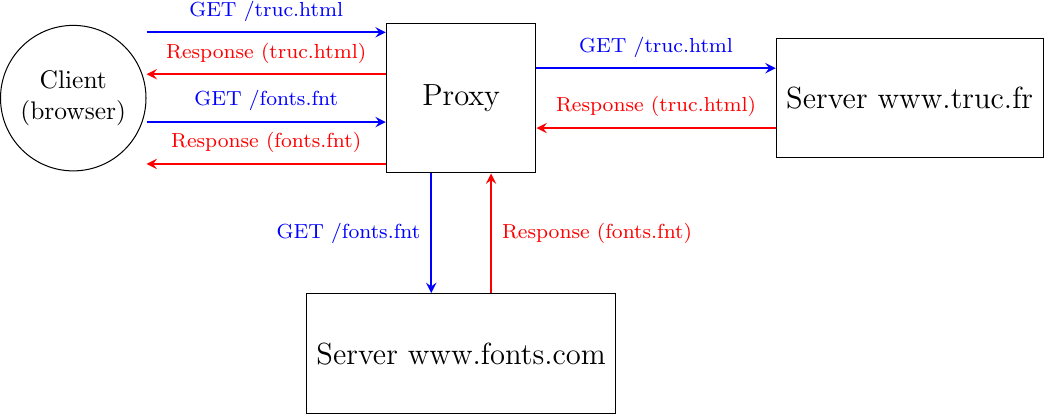

Proxies relay client requests to servers and return the received responses

Caches can also be used inside the network. To understand their benefits, let us consider an SME with a dozen of employees that are connected to the Internet through a low-speed link. These employees often access similar web sites. Consider that Alice and Bob want to browse today’s local newspaper. Their browsers will both retrieve the newspaper’s website through the low bandwidth link and store the main documents in their cache. Unfortunately, the same information passes twice over the low-speed link. Some companies have deployed web proxies to cope with this problem. A web proxy is a server that resides in the enterprise network. All the employee’s browsers are configured to send their HTTP requests to this proxy. When such a proxy receives a request, it checks whether the content is already stored inside its own cache. If so, it returns it directly. Otherwise, the request is sent to the remote server and the information is stored in the proxy cache. By reducing the number of web objects that are exchanged over low-speed links, such proxies can significantly improve performance. Some companies also use them to control the websites that are contacted by their employees and sometimes block illegitimate accesses.

Proxies can also be located in front of servers. In this case, they are called reverse-proxies. Consider a dynamic web server that produces web pages by assembling information stored in different databases. When this server receives a request, it must send multiple queries to its databases and then create the HTML document. These queries and the creation of the HTML document take time and this limits the number of requests that our server can sustain. Many content providers would place a reverse proxy in front of such a server. The DNS servers are configured to point to the reverse proxy. Upon reception of a request, the reverse proxy first checks whether the response is already stored in its cache. If so, it can return it to the client without interacting with the official server. Otherwise, the reverse proxy contacts the server and then returns the response to the client.

These reverse proxies can also be used to spread the load among different servers. In the above example, consider that a server needs 10 milliseconds to process each request and that it must handle them sequentially. Such a server cannot support more than 100 requests per second. If the service becomes popular, then the content provider will need to deploy several servers. These servers could serve the same reverse proxy.

Note

Serving content from multiple servers

When a web user interacts with www.service.net, she expects that all the information comes from the www.service.net server. If the service is popular, there are probably tens, hundreds, thousands or more physical servers that support this service. Still, the user has the illusion that she is interacting with a single server. Several techniques have been deployed by content providers to scale web services. Consider a simple service that serves text documents from N different servers. There are different ways to architect such a service.

A first approach is to store all files on each physical server and rely on the DNS to distribute the load among them. Each physical server has its own IP address and when the DNS server receives a query for www.service.net, it returns the IP address of one of them. Some DNS servers use Round-Robin to return one of these IP addresses. Others measure the load of the physical servers and return the address of the less loaded one. Another possibility is to locate the physical servers in different regions and configure the DNS server to return the IP address of the server that is geographically closer to the client’s IP address.

A second approach is to rely on k reverse proxies and N-k servers. The servers store the content and the proxies cache the most frequently used files. The proxies can be geographically close to the clients while the servers can reside in the datacenters of the content provider. The DNS server can also distribute the load among the different proxies or return the geographically closest proxy. An important point to note about reverse proxies is that they receive HTTP requests from clients and send HTTP requests to the original servers that host the content. Several companies, usually called Content Distribution Networks, have deployed such reverse proxies throughout the world to cache web content next to the end-users. A good description of such a CDN may be found in [NSS2010].

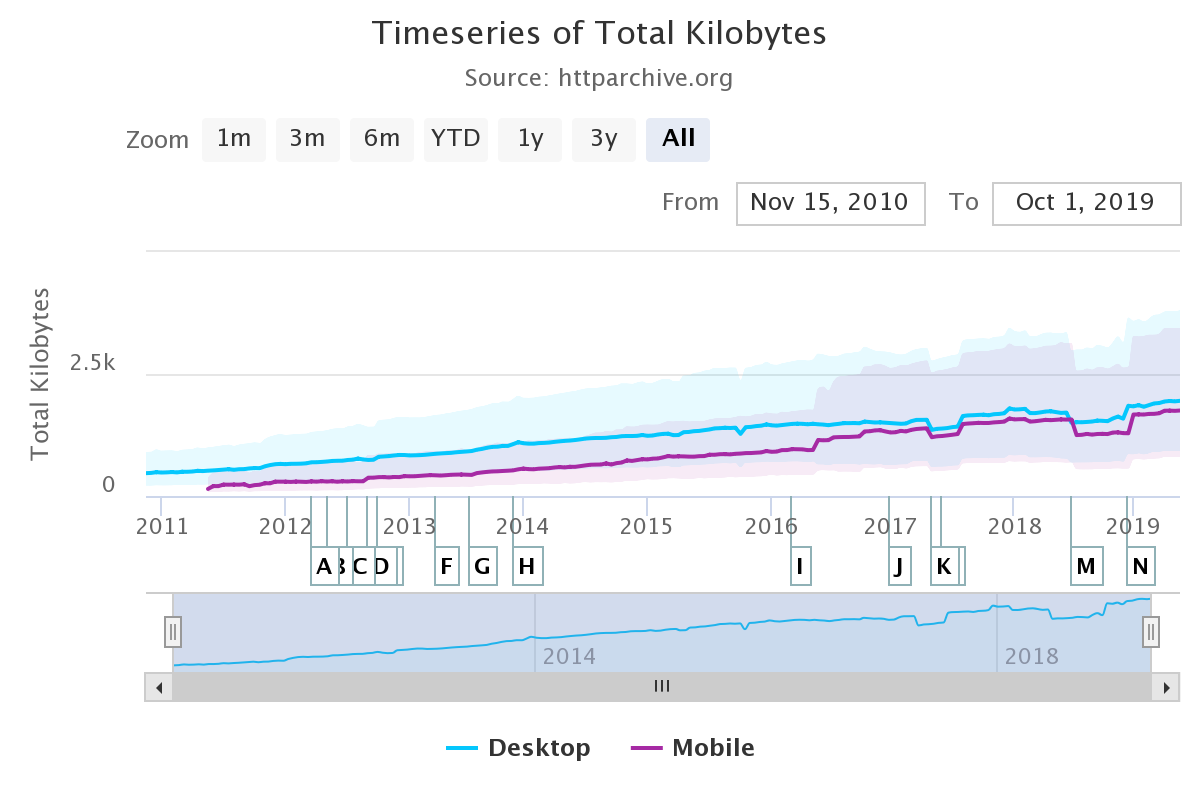

A second way to improve the web performance is to reduce the time required to retrieve web objects. While the first web servers returned an HTML documents with possibly a few images, today’s rich web servers return one HTML document with associated style sheets, javascript code, images, fonts, … Some of these web objects come from the original server while others are hosted on different servers. Today, a typical web page contains almost 2 MBytes of data on average. The size of the web pages continues to grow according to statistics collected by httparchive.org. Web pages targeted to mobile devices are slightly smaller.

Evolution of the size of the web pages (source: https://httparchive.org/reports/page-weight)¶

A closer look at the average web page shows that it contains, on average, 27 KBytes of HTML, 120 KBytes of fonts, 60 KBytes of CSS information, almost 1 MBytes of images and more than 400 KBytes of javascript. Each of these web page requires about 70 different HTTP requests. In other words, a browser needs to send on average 70 requests to retrieve a complete web page.

Two directions have been explored to improve the delivery of these web pages. The first direction is to tune the HTTP protocol. The second approach is to change the entire network stack. We will discuss this approach after having covered the entire stack.

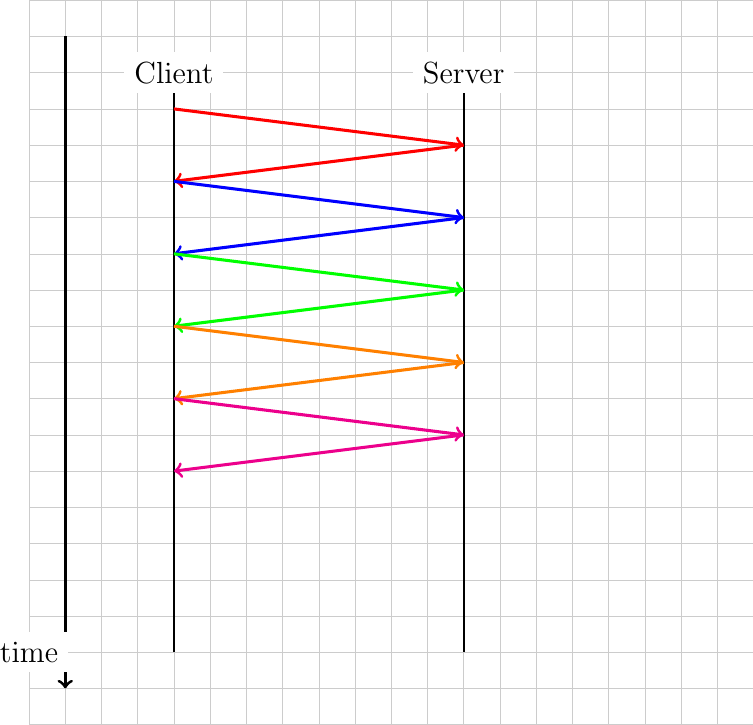

One of the limitations of HTTP from a performance viewpoint is that the requests that are sent by a browser must be sequential. Typically, a browser requests the HTML page. Once the page has been retrieved, the browser parses it to identify all the objects that it references and requests them one after each other. The web page can only be displayed to the user once all the required web objects have been retrieved. This implies that the browser must wait until the reception of each response before sending the next request. Another possibility is to allow the browser to send multiple requests without waiting for their corresponding responses. This approach is called pipelining in RFC 7230.

To understand the benefits of pipelining, let us consider a simple but illustrative example. A client needs to retrieve 5 web objects that are each 100 bytes. The underlying transport connection has a 1 Gbps bandwidth but a one-way delay of 100 msec. A normal HTTP/1.x client would send the first request, wait 200 msec to receive the answer, then send another request… It would need one entire second to retrieve the five web objects. This is illustrated in the figure below.

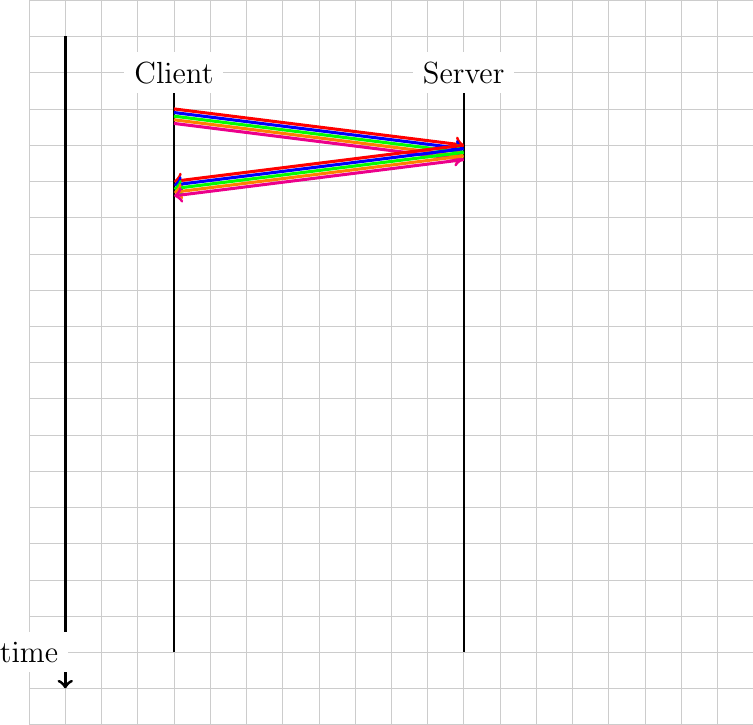

With pipelining, the client sends the five requests immediately and receives the five responses after 200 msec. The figure below illustrates the benefits of pipelining.

However, as explained in RFC 7230, there is one important limitation to pipelining. It can only be used to serve HTTP requests that are idempotent, i.e. none of the requests must depend on any of the previous requests in the pipeline. It turned out that it was difficult for web browsers to correctly support this requirement and very few of them have implemented pipelining 1.

Another limitation of HTTP/1.1 is that all commands and parameters are encoded as ASCII strings. Using ASCII strings makes it easy to write simple clients or debug problems by observing packets. Unfortunately, the burden is placed on servers that need to include complex parsers that accept a wide range of partially compliant implementations. Furthermore, the flexibility of the ASCII encoding has enabled some classes of security attacks on servers [CWE444].

To cope with these two problems, the IETF HTTP working group developed version 2.0 of HTTP. HTTP/2.0 diverges from HTTP/1.1 in two important ways. First, HTTP/2.0 relies on binary encoding which is both more compact and easier to parse. Second, HTTP/2.0 supports multiple streams, which makes it possible to simultaneously transfer different web objects over a single transport connection. Furthermore, HTTP/2.0 also compresses the HTTP headers to reduce the amount of data transferred. This technique is described in RFC 7541 but is not discussed in this chapter.

Let us first examine how HTTP/2.0 structures the bytestream of the underlying connection.

The HTTP/2.0 Frame header¶

The information exchanged over an HTTP/2.0 session is composed of frames. A frame starts with a 9 bytes-long header that carries several types of information. The HTTP/2.0 frames have a variable length. The Length field of the header contains the length of the frame payload in bytes. As this field is encoded as a 24 bits field, an HTTP/2.0 frame cannot be longer than \(2^{24} -1\) bytes. It should be noted that RFC 7540 assumes a maximum size of \(2^{14}\) bytes, i.e. 16,384 bytes for the HTTP/2.0 frame payload unless a longer maximum frame length has been negotiated at the beginning of the session using the HTTP/2.0 Settings frame that will be described later. The next field of the frames header indicates the frame type. The first frame types are Data which contains data from web objects and Headers containing HTTP/2.0 headers. When a client retrieves a web object from a server, it always receives an HTTP/2.0 Headers frame followed by an HTTP/2.0 Data frame. The Headers frame information contains essentially the same HTTP headers as the ones supported by HTTP/1.1, but those are encoded by leveraging a data compression technique that minimizes the number of bytes required to transmit them.

Other frame types are described later. The Flags are used for some frame types and the R bit must be set to zero. The last important field of the HTTP/2.0 Frame header is the Stream Identifier. With HTTP/2.0, the bytestream of the underlying transport connection is divided in independent streams that are identified by an integer. The odd (resp. even) stream identifiers are managed by the client (resp. server). This enables the server (or the client) to multiplex data corresponding to different frames over a single bytestream.

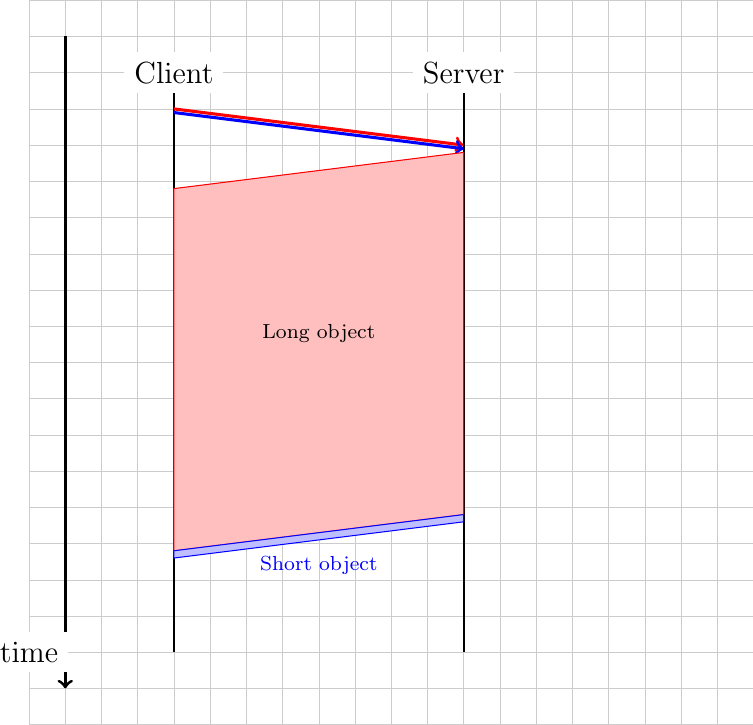

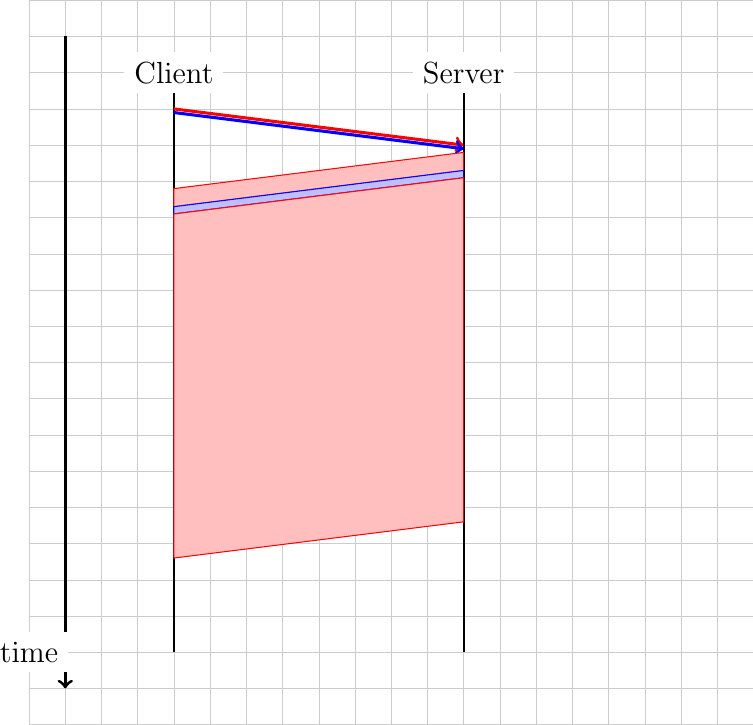

This multiplexing capability is probably the most important feature of HTTP/2.0 from a performance viewpoint. To understand its benefits, let us consider a client that retrieves two web objects over a 1 Mbps connection. The two requests are sent together by the client. The first object is 125 bytes long, while the second is 12500 bytes long. In this case, the server will first return the first object as a single frame and the second will be sent in the subsequent frame.

Consider now that the first object is 12500 bytes long and the second 125 bytes long. With a 1 Mbps connection, this object will use the underlying connection during 100 milliseconds. The client will thus need to wait 100 milliseconds to retrieve the second object. This is the Head of Line (HoL) blocking problem that affects the performance of many web services. If the short web object is a javascript code that requests other web objects, its retrieval may be critical to display the retrieved web page.

With HTTP/2.0 frames, the server could send the first 1250 bytes of the long object during 10 milliseconds, then send a second frame that contains the short object during one millisecond and later send a longer frame that contains the remaining 11250 bytes of the long object. In this case, the client has received the short object after 10 milliseconds. Given the HTTP/2.0 streams, the transmission of long web objects does not anymore blocks the transmission of shorter ones.

The length of the HTTP/2.0 frames obviously affects how different web objects can be multiplexed over the underlying transport connection. If HTTP/2.0 frames are long, the overhead of the frame header is minimal, but long frames can block short web objects. On the other hand, if the frame length is small, then the overhead due to the HTTP/2.0 frame header could become significant.

The HTTP/2.0 streams can provide performance benefits, but they also increase the complexity of the implementations since an HTTP/2.0 receiver must be able to simultaneously process frames that correspond to different web objects. This complexity mainly resides on the client side. The HTTP/2.0 protocol includes several techniques that enable clients to manage the utilization of the HTTP/2.0 session.

The first frame that a client sends over an HTTP/2.0 session is the Settings frame. This is a control frame that indicates some parameters that the client proposes for this session. Several of these parameters are defined in RFC 7540. The most important ones are probably the SETTINGS_MAX_FRAME_SIZE that specifies the maximum length of the HTTP/2.0 frames that this implementation supports and the SETTINGS_MAX_CONCURRENT_STREAMS that specifies the maximum number of parallel streams that this implementation can manage. The SETTINGS_MAX_FRAME_SIZE must be at least \(2^{14}\) bytes but can go up to \(2^{24} -1\) bytes. There is no minimum value for SETTINGS_MAX_CONCURRENT_STREAMS, but RFC 7540 recommends to support at least 100 different stream identifiers.

By using multiple streams, the server can multiplex different web objects over the same underlying transport connection. However, these objects are only sent in response to requests from clients. There are some situations where the server might know in advance that the client will request a given object. It could speedup the transfer by sending it before having received a client request. This is the push feature of HTTP/2.0. A server can independently push web objects to a client without having received any request. This feature can only be used by the server if the client has enabled it by sending SETTINGS_ENABLE_PUSH in its Settings frame. A classical use case for this push feature is to enable a server to automatically send an object which cannot be cached by the client, such as a dynamic javascript code, when another web object that references it is requested. However, measurement studies indicate that very few web servers seem to have adopted this feature [ZWH2018].

Another feature of HTTP/2.0 is that it is possible to assign different priorities to different streams. A high priority stream should carry more Data frames than a lower priority ones. The HTTP/2.0 specification defines Priority frames which can be used for this purpose.

As the server can send multiple objects at the same time, there is a risk of overloading the client buffers. To cope with this potential problem, HTTP/2.0 includes its own flow control mechanism. When an HTTP/2.0 session starts, a receiver agrees to receive up to 65,535 bytes over this connection (unless it has indicated a different initial window in its Settings frame). This limits the amount of data that a sender can transmit over the HTTP/2.0 session. The receiver can advertise a large receive window by sending a Window_Update frame at any time. This flow control mechanism can be applied to the entire connection or to a specific stream. In practice, using a small HTTP/2.0 window could severely limit the throughput over an HTTP/2.0 session.

HTTP/2.0 includes much more than what we have covered in this short introduction. There is for example a Ping frame that allows measuring the round-trip-time between a client and a server or the GoAway frame that indicates the termination of an HTTP/2.0 session. This frame contains an error code that indicates why the session has been terminated. Several error codes are defined in RFC 7540, including ENHANCE_YOUR_CALM that is used to indicate that the other endpoint exhibits an behavior that could cause excessive load.

Note

Detecting whether a server supports HTTP/2.0

HTTP/2.0 is a new version of the HTTP protocol that still uses port 80. When a client contacts an HTTP server, it must be able to determine whether it supports HTTP/1.x or HTTP/2.0. If the client sends a binary encoded HTTP/2.0 request to a server that only supports the ASCII encoded HTTP/1.x, it could cause problems on the server and even crash it. To minimize the risk of crashing HTTP/1.x servers, an HTTP/2.0 session starts like an HTTP/1.1 session and the first request contains the Connection, Upgrade and HTTP2-Settings headers. An example of such a request to upgrade the version of HTTP is shown below.

GET /robots.txt HTTP/1.1

Host: nghttp2.org

User-Agent: curl/7.52.1

Connection: Upgrade, HTTP2-Settings

Upgrade: h2c

HTTP2-Settings: AAMAAABkAARAAAAA

The HTTP2-Settings line contains the HTTP/2.0 settings frame that the client would server over an HTTP/2.0 session encoded in Base64. The server replies with a response that indicates that it has accepted to upgrade the connection to HTTP/2.0. A sample response is shown below.

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: h2c

Finally, the client and the server need to confirm the utilization of HTTP/2.0. A client confirms this by sending the following Magic string PRI * HTTP/2.0rnrnSMrnrn or 0x505249202a20485454502f322e300d0a0d0a534d0d0a0d0a in hex. This string is followed by a SETTINGS frame. The server must send a possibly empty SETTINGS frame.

Footnotes

- 1

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HTTP_pipelining for additional information.