Congestion control

Contents

Congestion control¶

In an internetwork, i.e. a networking composed of different types of networks (such as the Internet), congestion control could be implemented either in the network layer or the transport layer. The congestion problem was clearly identified in the later 1980s and the researchers who developed techniques to solve the problem opted for a solution in the transport layer. Adding congestion control to the transport layer makes sense since this layer provides a reliable data transfer and avoiding congestion is a factor in this reliable delivery. The transport layer already deals with heterogeneous networks thanks to its self-clocking property that we have already described. In this section, we explain how congestion control has been added to TCP and how this mechanism could be improved in the future.

The TCP congestion control scheme was initially proposed by Van Jacobson in [Jacobson1988]. The current specification may be found in RFC 5681. TCP relies on Additive Increase and Multiplicative Decrease (AIMD). To implement AIMD, a TCP host must be able to control its transmission rate. A first approach would be to use timers and adjust their expiration times in function of the rate imposed by AIMD. Unfortunately, maintaining such timers for a large number of TCP connections can be difficult. Instead, Van Jacobson noted that the rate of TCP congestion can be artificially controlled by constraining its sending window. A TCP connection cannot send data faster than \(\frac{window}{rtt}\) where \(window\) is the minimum between the host’s sending window and the window advertised by the receiver.

TCP’s congestion control scheme is based on a congestion window. The current value of the congestion window (cwnd) is stored in the TCB of each TCP connection and the window that can be used by the sender is constrained by \(\min(cwnd,rwin,swin)\) where \(swin\) is the current sending window and \(rwin\) the last received receive window. The Additive Increase part of the TCP congestion control increments the congestion window by MSS bytes every round-trip-time. In the TCP literature, this phase is often called the congestion avoidance phase. The Multiplicative Decrease part of the TCP congestion control divides the current value of the congestion window once congestion has been detected.

When a TCP connection begins, the sending host does not know whether the part of the network that it uses to reach the destination is congested or not. To avoid causing too much congestion, it must start with a small congestion window. [Jacobson1988] recommends an initial window of MSS bytes. As the additive increase part of the TCP congestion control scheme increments the congestion window by MSS bytes every round-trip-time, the TCP connection may have to wait many round-trip-times before being able to efficiently use the available bandwidth. This is especially important in environments where the \(bandwidth \times rtt\) product is high. To avoid waiting too many round-trip-times before reaching a congestion window that is large enough to efficiently utilize the network, the TCP congestion control scheme includes the slow-start algorithm. The objective of the TCP slow-start phase is to quickly reach an acceptable value for the cwnd. During slow-start, the congestion window is doubled every round-trip-time. The slow-start algorithm uses an additional variable in the TCB : ssthresh (slow-start threshold). The ssthresh is an estimation of the last value of the cwnd that did not cause congestion. It is initialized at the sending window and is updated after each congestion event.

A key question that must be answered by any congestion control scheme is how congestion is detected. The first implementations of the TCP congestion control scheme opted for a simple and pragmatic approach : packet losses indicate congestion. If the network is congested, router buffers are full and packets are discarded. In wired networks, packet losses are mainly caused by congestion. In wireless networks, packets can be lost due to transmission errors and for other reasons that are independent of congestion. TCP already detects segment losses to ensure a reliable delivery. The TCP congestion control scheme distinguishes between two types of congestion :

mild congestion. TCP considers that the network is lightly congested if it receives three duplicate acknowledgments and performs a fast retransmit. If the fast retransmit is successful, this implies that only one segment has been lost. In this case, TCP performs multiplicative decrease and the congestion window is divided by 2. The slow-start threshold is set to the new value of the congestion window.

severe congestion. TCP considers that the network is severely congested when its retransmission timer expires. In this case, TCP retransmits the first segment, sets the slow-start threshold to 50% of the congestion window. The congestion window is reset to its initial value and TCP performs a slow-start.

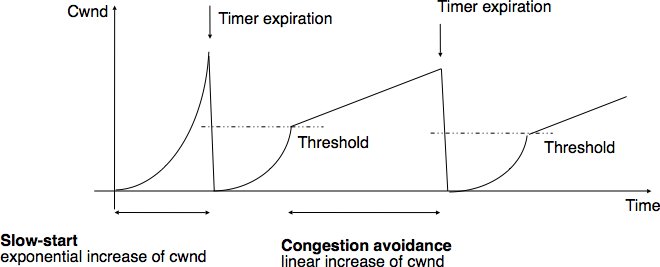

The figure below illustrates the evolution of the congestion window when there is severe congestion. At the beginning of the connection, the sender performs slow-start until the first segments are lost and the retransmission timer expires. At this time, the ssthresh is set to half of the current congestion window and the congestion window is reset at one segment. The lost segments are retransmitted as the sender again performs slow-start until the congestion window reaches the sshtresh. It then switches to congestion avoidance and the congestion window increases linearly until segments are lost and the retransmission timer expires.

Evaluation of the TCP congestion window with severe congestion¶

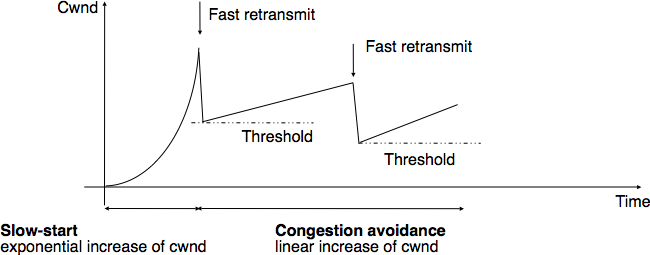

The figure below illustrates the evolution of the congestion window when the network is lightly congested and all lost segments can be retransmitted using fast retransmit. The sender begins with a slow-start. A segment is lost but successfully retransmitted by a fast retransmit. The congestion window is divided by 2 and the sender immediately enters congestion avoidance as this was a mild congestion.

Evaluation of the TCP congestion window when the network is lightly congested¶

Most TCP implementations update the congestion window when they receive an acknowledgment. If we assume that the receiver acknowledges each received segment and the sender only sends MSS sized segments, the TCP congestion control scheme can be implemented using the simplified pseudo-code 1 below. This pseudocode includes the optimization proposed in RFC 3042 that allows a sender to send new unsent data upon reception of the first or second duplicate acknowledgment. The reception of each of these acknowledgments indicates that one segment has left the network and thus additional data can be sent without causing more congestion. Note that the congestion window is not increased upon reception of these first duplicate acknowledgments.

# Initialization

cwnd = MSS # congestion window in bytes

ssthresh= swin # in bytes

# Ack arrival

if tcp.ack > snd.una: # new ack, no congestion

if dupacks == 0: # not currently recovering from loss

if cwnd < ssthresh:

# slow-start : quickly increase cwnd

# double cwnd every rtt

cwnd = cwnd + MSS

else:

# congestion avoidance : slowly increase cwnd

# increase cwnd by one mss every rtt

cwnd = cwnd + MSS * (MSS / cwnd)

else: # recovering from loss

cwnd = ssthresh # deflate cwnd RFC5681

dupacks = 0

else: # duplicate or old ack

if tcp.ack == snd.una: # duplicate acknowledgment

dupacks += 1

if dupacks == 1 or dupacks == 2:

send_next_unacked_segment # RFC3042

if dupacks == 3:

retransmitsegment(snd.una)

ssthresh = max(cwnd/2, 2*MSS)

cwnd = ssthresh

if dupacks > 3: # RFC5681

cwnd = cwnd + MSS # inflate cwnd

else:

# ack for old segment, ignored

pass

Expiration of the retransmission timer:

send(snd.una) # retransmit first lost segment

sshtresh = max(cwnd/2, 2*MSS)

cwnd = MSS

Furthermore when a TCP connection has been idle for more than its current retransmission timer, it should reset its congestion window to the congestion window size that it uses when the connection begins, as it no longer knows the current congestion state of the network.

Note

Initial congestion window

The original TCP congestion control mechanism proposed in [Jacobson1988] recommended that each TCP connection should begin by setting \(cwnd=MSS\). However, in today’s higher bandwidth networks, using such a small initial congestion window severely affects the performance for short TCP connections, such as those used by web servers. In 2002, RFC 3390 allowed an initial congestion window of about 4 KBytes, which corresponds to 3 segments in many environments. Recently, researchers from Google proposed to further increase the initial window up to 15 KBytes [DRC+2010]. The measurements that they collected show that this increase would not significantly increase congestion but would significantly reduce the latency of short HTTP responses. Unsurprisingly, the chosen initial window corresponds to the average size of an HTTP response from a search engine. This proposed modification has been adopted in RFC 6928 and TCP implementations support it.

Controlling congestion without losing data¶

In today’s Internet, congestion is controlled by regularly sending packets at a higher rate than the network capacity. These packets fill the buffers of the routers and are eventually discarded. But shortly after, TCP senders retransmit packets containing exactly the same data. This is potentially a waste of resources since these successive retransmissions consume resources upstream of the router that discards the packets. Packet losses are not the only signal to detect congestion inside the network. An alternative is to allow routers to explicitly indicate their current level of congestion when forwarding packets. This approach was proposed in the late 1980s [RJ1995] and used in some networks. Unfortunately, it took almost a decade before the Internet community agreed to consider this approach. In the mean time, a large number of TCP implementations and routers were deployed on the Internet.

As explained earlier, Explicit Congestion Notification RFC 3168 improves the detection of congestion by allowing routers to explicitly mark packets when they are lightly congested. In theory, a single bit in the packet header [RJ1995] is sufficient to support this congestion control scheme. When a host receives a marked packet, it returns the congestion information to the source that adapts its transmission rate accordingly. Although the idea is relatively simple, deploying it on the entire Internet has proven to be challenging [KNT2013]. It is interesting to analyze the different factors that have hindered the deployment of this technique.

The first difficulty in adding Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) in TCP/IP network was to modify the format of the network packet and transport segment headers to carry the required information. In the network layer, one bit was required to allow the routers to mark the packets they forward during congestion periods. In the IP network layer, this bit is called the Congestion Experienced (CE) bit and is part of the packet header. However, using a single bit to mark packets is not sufficient. Consider a simple scenario with two sources, one congested router and one destination. Assume that the first sender and the destination support ECN, but not the second sender. If the router is congested it will mark packets from both senders. The first sender will react to the packet markings by reducing its transmission rate. However since the second sender does not support ECN, it will not react to the markings. Furthermore, this sender could continue to increase its transmission rate, which would lead to more packets being marked and the first source would decrease again its transmission rate, … In the end, the sources that implement ECN are penalized compared to the sources that do not implement it. This unfairness issue is a major hurdle to widely deploy ECN on the public Internet 2. The solution proposed in RFC 3168 to deal with this problem is to use a second bit in the network packet header. This bit, called the ECN-capable transport (ECT) bit, indicates whether the packet contains a segment produced by a transport protocol that supports ECN or not. Transport protocols that support ECN set the ECT bit in all packets. When a router is congested, it first verifies whether the ECT bit is set. In this case, the CE bit of the packet is set to indicate congestion. Otherwise, the packet is discarded. This eases the deployment of ECN 3.

The second difficulty is how to allow the receiver to inform the sender of the reception of network packets marked with the CE bit. In reliable transport protocols like TCP and SCTP, the acknowledgments can be used to provide this feedback. For TCP, two options were possible : change some bits in the TCP segment header or define a new TCP option to carry this information. The designers of ECN opted for reusing spare bits in the TCP header. More precisely, two TCP flags have been added in the TCP header to support ECN. The ECN-Echo (ECE) is set in the acknowledgments when the CE was set in packets received on the forward path.

The TCP flags¶

The third difficulty is to allow an ECN-capable sender to detect whether the remote host also supports ECN. This is a classical negotiation of extensions to a transport protocol. In TCP, this could have been solved by defining a new TCP option used during the three-way handshake. To avoid wasting space in the TCP options, the designers of ECN opted in RFC 3168 for using the ECN-Echo and CWR bits in the TCP header to perform this negotiation. In the end, the result is the same with fewer bits exchanged.

Thanks to the ECT, CE and ECE, routers can mark packets during congestion and receivers can return the congestion information back to the TCP senders. However, these three bits are not sufficient to allow a server to reliably send the ECE bit to a TCP sender. TCP acknowledgments are not sent reliably. A TCP acknowledgment always contains the next expected sequence number. Since TCP acknowledgments are cumulative, the loss of one acknowledgment is recovered by the correct reception of a subsequent acknowledgment.

If TCP acknowledgments are overloaded to carry the ECE bit, the situation is different. Consider the example shown in the figure below. A client sends packets to a server through a router. In the example below, the first packet is marked. The server returns an acknowledgment with the ECE bit set. Unfortunately, this acknowledgment is lost and never reaches the client. Shortly after, the server sends a data segment that also carries a cumulative acknowledgment. This acknowledgment confirms the reception of the data to the client, but it did not receive the congestion information through the ECE bit.

To solve this problem, RFC 3168 uses an additional bit in the TCP header : the Congestion Window Reduced (CWR) bit.

The CWR bit of the TCP header provides some form of acknowledgment for the ECE bit. When a TCP receiver detects a packet marked with the CE bit, it sets the ECE bit in all segments that it returns to the sender. Upon reception of an acknowledgment with the ECE bit set, the sender reduces its congestion window to reflect a mild congestion and sets the CWR bit. This bit remains set as long as the segments received contained the ECE bit set. A sender should only react once per round-trip-time to marked packets.

The last point that needs to be discussed about Explicit Congestion Notification is the algorithm that is used by routers to detect congestion. On a router, congestion manifests itself by the number of packets that are stored inside the router buffers. As explained earlier, we need to distinguish between two types of routers :

routers that have a single FIFO queue

routers that have several queues served by a round-robin scheduler

Routers that use a single queue measure their buffer occupancy as the number of bytes of packets stored in the queue 4. A first method to detect congestion is to measure the instantaneous buffer occupancy and consider the router to be congested as soon as this occupancy is above a threshold. Typical values of the threshold could be 40% of the total buffer. Measuring the instantaneous buffer occupancy is simple since it only requires one counter. However, this value is fragile from a control viewpoint since it changes frequently. A better solution is to measure the average buffer occupancy and consider the router to be congested when this average occupancy is too high. Random Early Detection (RED) [FJ1993] is an algorithm that was designed to support Explicit Congestion Notification. In addition to measuring the average buffer occupancy, it also uses probabilistic marking. When the router is congested, the arriving packets are marked with a probability that increases with the average buffer occupancy. The main advantage of using probabilistic marking instead of marking all arriving packets is that flows will be marked in proportion of the number of packets that they transmit. If the router marks 10% of the arriving packets when congested, then a large flow that sends hundred packets per second will be marked 10 times while a flow that only sends one packet per second will not be marked. This probabilistic marking allows marking packets in proportion of their usage of the network resources.

If the router uses several queues served by a scheduler, the situation is different. If a large and a small flow are competing for bandwidth, the scheduler will already favor the small flow that is not using its fair share of the bandwidth. The queue for the small flow will be almost empty while the queue for the large flow will build up. On routers using such schedulers, a good way of marking the packets is to set a threshold on the occupancy of each queue and mark the packets that arrive in a particular queue as soon as its occupancy is above the configured threshold.

Modeling TCP congestion control¶

Thanks to its congestion control scheme, TCP adapts its transmission rate to the losses that occur in the network. Intuitively, the TCP transmission rate decreases when the percentage of losses increases. Researchers have proposed detailed models that allow the prediction of the throughput of a TCP connection when losses occur [MSMO1997] . To have some intuition about the factors that affect the performance of TCP, let us consider a very simple model. Its assumptions are not completely realistic, but it gives us good intuition without requiring complex mathematics.

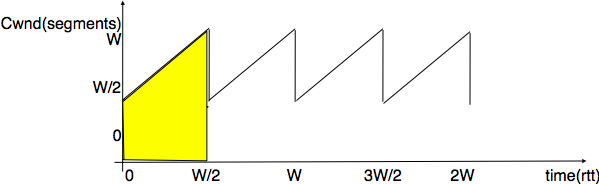

This model considers a hypothetical TCP connection that suffers from equally spaced segment losses. If \(p\) is the segment loss ratio, then the TCP connection successfully transfers \(\frac{1}{p}-1\) segments and the next segment is lost. If we ignore the slow-start at the beginning of the connection, TCP in this environment is always in congestion avoidance as there are only isolated losses that can be recovered by using fast retransmit. The evolution of the congestion window is thus as shown in the figure below. Note that the x-axis of this figure represents time measured in units of one round-trip-time, which is supposed to be constant in the model, and the y-axis represents the size of the congestion window measured in MSS-sized segments.

Evolution of the congestion window with regular losses¶

As the losses are equally spaced, the congestion window always starts at some value (\(\frac{W}{2}\)), and is incremented by one MSS every round-trip-time until it reaches twice this value (W). At this point, a segment is retransmitted and the cycle starts again. If the congestion window is measured in MSS-sized segments, a cycle lasts \(\frac{W}{2}\) round-trip-times. The bandwidth of the TCP connection is the number of bytes that have been transmitted during a given period of time. During a cycle, the number of segments that are sent on the TCP connection is equal to the area of the yellow trapeze in the figure. Its area is thus :

\(area=(\frac{W}{2})^2 + \frac{1}{2} \times (\frac{W}{2})^2 = \frac{3 \times W^2}{8}\)

However, given the regular losses that we consider, the number of segments that are sent between two losses (i.e. during a cycle) is by definition equal to \(\frac{1}{p}\). Thus, \(W=\sqrt{\frac{8}{3 \times p}}=\frac{k}{\sqrt{p}}\). The throughput (in bytes per second) of the TCP connection is equal to the number of segments transmitted divided by the duration of the cycle :

\(Throughput=\frac{area \times MSS}{time} = \frac{ \frac{3 \times W^2}{8}}{\frac{W}{2} \times rtt}\) or, after having eliminated W, \(Throughput=\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}} \times \frac{MSS}{rtt \times \sqrt{p}}\)

More detailed models and the analysis of simulations have shown that a first order model of the TCP throughput when losses occur was \(Throughput \approx \frac{k \times MSS}{rtt \times \sqrt{p}}\). This is an important result which shows that :

TCP connections with a small round-trip-time can achieve a higher throughput than TCP connections having a longer round-trip-time when losses occur. This implies that the TCP congestion control scheme is not completely fair since it favors the connections that have the shorter round-trip-times.

TCP connections that use a large MSS can achieve a higher throughput that the TCP connections that use a shorter MSS. This creates another source of unfairness between TCP connections. However, it should be noted that today most hosts are using almost the same MSS, roughly 1460 bytes.

In general, the maximum throughput that can be achieved by a TCP connection depends on its maximum window size and the round-trip-time if there are no losses. If there are losses, it depends on the MSS, the round-trip-time and the loss ratio.

\(Throughput<\min(\frac{window}{rtt},\frac{k \times MSS}{rtt \times \sqrt{p}})\)

Note

The TCP congestion control zoo

The first TCP congestion control scheme was proposed by Van Jacobson in [Jacobson1988]. In addition to writing the scientific paper, Van Jacobson also implemented the slow-start and congestion avoidance schemes in release 4.3 Tahoe of the BSD Unix distributed by the University of Berkeley. Later, he improved the congestion control by adding the fast retransmit and the fast recovery mechanisms in the Reno release of 4.3 BSD Unix. Since then, many researchers have proposed, simulated and implemented modifications to the TCP congestion control scheme. Some of these modifications are still used today, e.g. :

NewReno (RFC 3782), which was proposed as an improvement of the fast recovery mechanism in the Reno implementation.

TCP Vegas, which uses changes in the round-trip-time to estimate congestion in order to avoid it [BOP1994]. This is one of the examples of the delay-based congestion control algorithms. A Vegas sender continuously measures the evolution of the round-trip-time and slows down when the round-trip-time increases significantly. This enables Vegas to prevent congestion when used alone. Unfortunately, if Vegas senders compete with more aggressive TCP congestion control schemes that only react to losses, Vegas senders may have difficulties to use their fair share of the available bandwidth.

CUBIC, which was designed for high bandwidth links and is the default congestion control scheme in Linux since the Linux 2.6.19 kernel [HRX2008]. It is now used by several operating systems and is becoming the default congestion control scheme RFC 8312. A key difference between CUBIC and the TCP congestion control scheme described in this chapter is that CUBIC is much more aggressive when probing the network. Instead of relying on additive increase after a fast recovery, a CUBIC sender adjusts its congestion by using a cubic function. Thanks to this function, the congestion windows grows faster. This is particularly important in high-bandwidth delay networks.

BBR, which is being developed by Google researchers and is included in recent Linux kernels [CCG+2016]. BBR periodically estimates the available bandwidth and the round-trip-times. To adapt to changes in network conditions, BBR regularly tries to send at 1.25 times the current bandwidth. This enables BBR senders to probe the network, but can also cause large amount of losses. Recent scientific articles indicate that BBR is unfair to other congestion control schemes in specific conditions [WMSS2019].

A wide range of congestion control schemes have been proposed in the scientific literature and several of them have been widely deployed. A detailed comparison of these congestion control schemes is outside the scope of this chapter. A recent survey paper describing many of the implemented TCP congestion control schemes may be found in [TKU2019].

Footnotes

- 1

In this pseudo-code, we assume that TCP uses unlimited sequence and acknowledgment numbers. Furthermore, we do not detail how the cwnd is adjusted after the retransmission of the lost segment by fast retransmit. Additional details may be found in RFC 5681.

- 2

In enterprise networks or datacenters, the situation is different since a single company typically controls all the sources and all the routers. In such networks it is possible to ensure that all hosts and routers have been upgraded before turning on ECN on the routers.

- 3

With the ECT bit, the deployment issue with ECN is solved provided that all sources cooperate. If some sources do not support ECN but still set the ECT bit in the packets that they sent, they will have an unfair advantage over the sources that correctly react to packet markings. Several solutions have been proposed to deal with this problem RFC 3540, but they are outside the scope of this book.

- 4

The buffers of a router can be implemented as variable or fixed-length slots. If the router uses variable length slots to store the queued packets, then the occupancy is usually measured in bytes. Some routers have use fixed-length slots with each slot large enough to store a maximum-length packet. In this case, the buffer occupancy is measured in packets.

![msc {

client [label="client", linecolour=black],

router [label="router", linecolour=black],

server [label="server", linecolour=black];

client=>router [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1" ];

router=>server [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=1]", arcskip="1"];

|||;

server=>router [ label = "ack=2,ECE=1", arcskip="1" ];

router -x client [label="ack=2,ECE=1", arcskip="1" ];

|||;

server=>router [ label = "data[seq=x,ack=2,ECE=0,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1" ];

router=>client [ label = "data[seq=x,ack=2,ECE=0,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1"];

|||;

client->server [linecolour=white];

}](../_images/mscgen-700c52eed1dd99ea5abd5216ffd2e044e6fee931.png)

![msc {

client [label="client", linecolour=black],

router [label="router", linecolour=black],

server [label="server", linecolour=black];

client=>router [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1" ];

router=>server [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=1]", arcskip="1"];

|||;

server=>router [ label = "ack=2,ECE=1", arcskip="1" ];

router -x client [label="ack=2,ECE=1", arcskip="1" ];

|||;

server=>router [ label = "data[seq=x,ack=2,ECE=1,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1" ];

router=>client [ label = "data[seq=x,ack=2,ECE=1,ECT=1,CE=0]", arcskip="1"];

|||;

client=>router [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=0,CWR=1]", arcskip="1" ];

router=>server [ label = "data[seq=1,ECT=1,CE=1,CWR=1]", arcskip="1"];

|||;

client->server [linecolour=white];

}](../_images/mscgen-d60c580a7379dbdd26f90fd2eead54f832ee6ad6.png)