Naming and addressing

Contents

Naming and addressing¶

The network and the transport layers rely on addresses that are encoded as fixed size bit strings. A network layer address uniquely identifies a host. Several transport layer entities can use the service of the same network layer. For example, a reliable transport protocol and a connectionless transport protocol can coexist on the same host. In this case, the network layer multiplexes the segments produced by these two protocols. This multiplexing is usually achieved by placing in the network packet header a field that indicates which transport protocol should process the segment. Given that there are few different transport protocols, this field does not need to be long. The port numbers play a similar role in the transport layer since they enable it to multiplex data from several application processes.

While addresses are natural for the network and transport layer entities, humans prefer to use names when interacting with network services. Names can be encoded as a character string and a mapping services allows applications to map a name into the corresponding address. Using names is friendlier for humans, but it also provides a level of indirection which is very useful in many situations.

In the early days of the Internet, only a few hosts (mainly minicomputers) were connected to the network. The most popular applications were remote login and file transfer. By 1983, there were already five hundred hosts attached to the Internet [Zakon]. Each of these hosts were identified by a unique address. Forcing human users to remember the addresses of the hosts that they wanted to use was not user-friendly. Humans prefer to remember names, and use them when needed. Using names as aliases for addresses is a common technique in Computer Science. It simplifies the development of applications and allows the developer to ignore the low level details. For example, by using a programming language instead of writing machine code, a developer can write software without knowing whether the variables that it uses are stored in memory or inside registers.

Because names are at a higher level than addresses, they allow (both in the example of programming above, and on the Internet) to treat addresses as mere technical identifiers, which can change at will. Only the names are stable.

The first solution that allowed applications to use names was the hosts.txt file. This file is similar to the symbol table found in compiled code. It contains the mapping between the name of each Internet host and its associated address 1. It was maintained by the SRI International Network Information Center (NIC). When a new host was connected to the network, the system administrator had to register its name and address at the NIC. The NIC updated the hosts.txt file on its server. All Internet hosts regularly retrieved the updated hosts.txt file from the SRI server. This file was stored at a well-known location on each Internet host (see RFC 952) and networked applications could use it to find the address corresponding to a name.

A hosts.txt file can be used when there are up to a few hundred hosts on the network. However, it is clearly not suitable for a network containing thousands or millions of hosts. A key issue in a large network is to define a suitable naming scheme. The ARPANet initially used a flat naming space, i.e. each host was assigned a unique name. To limit collisions between names, these names usually contained the name of the institution and a suffix to identify the host inside the institution (a kind of poor man’s hierarchical naming scheme). On the ARPANet few institutions had several hosts connected to the network.

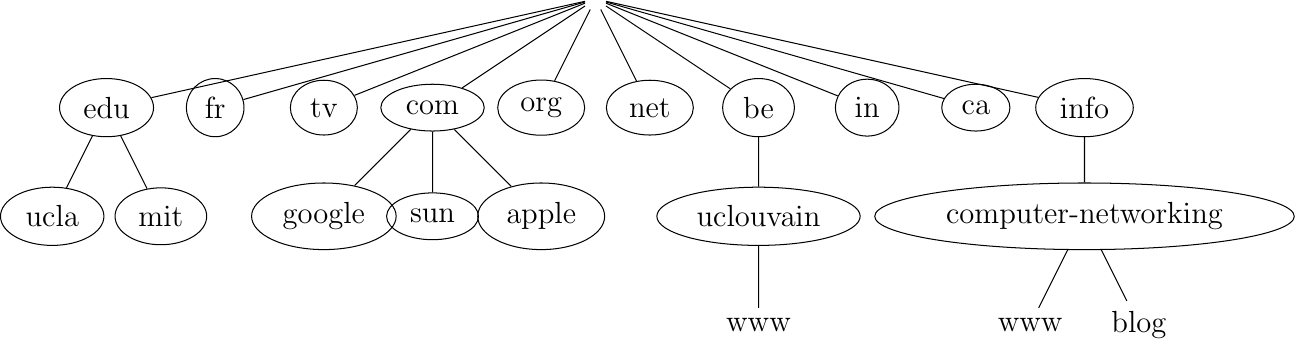

However, the limitations of a flat naming scheme became clear before the end of the ARPANet and RFC 819 proposed a hierarchical naming scheme. While RFC 819 discussed the possibility of organizing the names as a directed graph, the Internet opted for a tree structure capable of containing all names. In this tree, the top-level domains are those that are directly attached to the root. The first top-level domain was .arpa 2. This top-level name was initially added as a suffix to the names of the hosts attached to the ARPANet and listed in the hosts.txt file. In 1984, the .gov, .edu, .com, .mil and .org generic top-level domain names were added. RFC 1032 proposed the utilization of the two letter ISO-3166 country codes as top-level domain names. Since ISO-3166 defines a two letter code for each country recognized by the United Nations, this allowed all countries to automatically have a top-level domain. These domains include .be for Belgium, .fr for France, .us for the USA, .ie for Ireland or .tv for Tuvalu, a group of small islands in the Pacific or .tm for Turkmenistan. The set of top-level domain-names is managed by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). ICANN adds generic top-level domains that are not related to a country and the .cat top-level domain has been registered for the Catalan language. There are ongoing discussions within ICANN to increase the number of top-level domains.

Each top-level domain is managed by an organization that decides how sub-domain names can be registered. Most top-level domain names use a first-come first served system, and allow anyone to register domain names, but there are some exceptions. For example, .gov is reserved for the US government, .int is reserved for international organizations and names in the .ca are mainly reserved for companies or users that are present in Canada.

The tree of domain names

The syntax of the domain names has been defined more precisely in RFC 1035. This document recommends the following BNF for fully qualified domain names (the domain names themselves have a much richer syntax).

domain ::= subdomain | " "

subdomain ::= label | subdomain "." label

label ::= letter [ [ ldh-str ] let-dig ]

ldh-str ::= let-dig-hyp | let-dig-hyp ldh-str

let-dig-hyp ::= let-dig | "-"

let-dig ::= letter | digit

letter ::= any one of the 52 alphabetic characters A through Z in upper case and a through z in lower case

digit ::= any one of the ten digits 0 through 9

This grammar specifies that a host name is an ordered list of labels separated by the dot (.) character. Each label can contain letters, numbers and the hyphen character (-) 3. Fully qualified domain names are read from left to right. The first label is a hostname or a domain name followed by the hierarchy of domains and ending with the root implicitly at the right. The top-level domain name must be one of the registered TLDs 4. For example, in the above figure, www.computer-networking.info corresponds to a host named www inside the computer-networking domain that belongs to the info top-level domain.

Note

Some visually similar characters have different character codes

The Domain Name System was created at a time when the Internet was mainly used in North America. The initial design assumed that all domain names would be composed of letters and digits RFC 1035. As Internet usage grew in other parts of the world, it became important to support non-ASCII characters. For this, extensions have been proposed to the Domain Name System RFC 3490. In a nutshell, the solution that is used to support Internationalized Domain Names works as follows. First, it is possible to use most of the Unicode characters to encode domain names and hostnames, with a few exceptions (for example, the dot character cannot be part of a name since it is used as a separator). Once a domain name has been encoded as a series of Unicode characters, it is then converted into a string that contains the xn-- prefix and a sequence of ASCII characters. More details on these algorithms can be found in RFC 3490 and RFC 3492.

The possibility of using all Unicode characters to create domain names opened a new form of attack called the homograph attack. This attack occurs when two character strings or domain names are visually similar but do not correspond to the same server. A simple example is https://G00GLE.COM and https://GOOGLE.COM. These two URLs are visually close but they correspond to different names (the first one does not point to a valid server 5). With other Unicode characters, it is possible to construct domain names are visually equivalent to existing ones. See [Zhe2017] for additional details on this attack.

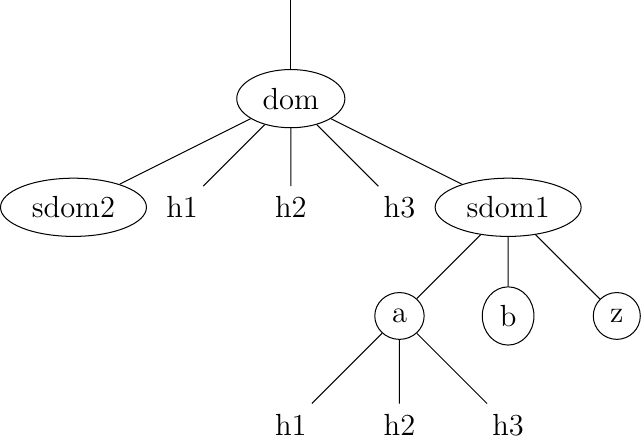

This hierarchical naming scheme is a key component of the Domain Name System (DNS). The DNS is a distributed database that contains mappings between fully qualified domain names and addresses. The DNS uses the client-server model. The clients are hosts or applications that need to retrieve the mapping for a given name. Each nameserver stores part of the distributed database and answers the queries sent by clients. There is at least one nameserver that is responsible for each domain. In the figure below, domains are represented by circles and there are three hosts inside domain dom (h1, h2 and h3) and three hosts inside domain a.sdom1.dom. As shown in the figure below, a sub-domain may contain both host names and sub-domains.

A simple tree of domain names

A nameserver that is responsible for domain dom can directly answer the following queries :

the address of any host residing directly inside domain dom (e.g. h2.dom in the figure above)

the nameserver(s) that are responsible for any direct sub-domain of domain dom (i.e. sdom1.dom and sdom2.dom in the figure above, but not z.sdom1.dom)

To retrieve the mapping for host h2.dom, a client sends its query to the name server that is responsible for domain .dom. The name server directly answers the query. To retrieve a mapping for h3.a.sdom1.dom a DNS client first sends a query to the name server that is responsible for the .dom domain. This nameserver returns the nameserver that is responsible for the sdom1.dom domain. This nameserver can now be contacted to obtain the nameserver that is responsible for the a.sdom1.dom domain. This nameserver can be contacted to retrieve the mapping for the h3.a.sdom1.dom name. Thanks to this structure, it is possible for a DNS client to obtain the mapping of any host inside the .dom domain or any of its subdomains. To ensure that any DNS client will be able to resolve any fully qualified domain name, there are special nameservers that are responsible for the root of the domain name hierarchy. These nameservers are called root nameserver.

Each root nameserver maintains the list 6 of all the nameservers that are responsible for each of the top-level domain names and their addresses 7. All root nameservers cooperate and provide the same answers. By querying any of the root nameservers, a DNS client can obtain the nameserver that is responsible for any top-level-domain name. From this nameserver, it is possible to resolve any domain name.

To be able to contact the root nameservers, each DNS client must know their addresses. This implies, that DNS clients must maintain an up-to-date list of the addresses of the root nameservers. Without this list, it is impossible to contact the root nameservers. Forcing all Internet hosts to maintain the most recent version of this list would be difficult from an operational point of view. To solve this problem, the designers of the DNS introduced a special type of DNS server : the DNS resolvers. A resolver is a server that provides the name resolution service for a set of clients. A network usually contains a few resolvers. Each host in these networks is configured to send all its DNS queries via one of its local resolvers. These queries are called recursive queries as the resolver must recursively send requests through the hierarchy of nameservers to obtain the answer.

DNS resolvers have several advantages over letting each Internet host query directly nameservers. Firstly, regular Internet hosts do not need to maintain the up-to-date list of the addresses of the root servers. Secondly, regular Internet hosts do not need to send queries to nameservers all over the Internet. Furthermore, as a DNS resolver serves a large number of hosts, it can cache the received answers. This allows the resolver to quickly return answers for popular DNS queries and reduces the load on all DNS servers [JSBM2002].

Benefits of names¶

In addition to being more human friendly, using names instead of addresses inside applications has several important benefits. To understand them, let us consider a popular application that provides information stored on servers. This application involves clients and servers. The server provides information upon requests from client processes. A first deployment of this application would be to rely only on addresses. In this case, the server process would be installed on one host and the clients would connect to this server to retrieve information. Such a deployment has several drawbacks :

if the server process moves to another physical server, all clients must be informed about the new server address

if there are many concurrent clients, the load of the server will increase without any possibility of adding another server without changing the server addresses used by the clients

Using names solves these problems and provides additional benefits. If the clients are configured with the name of the server, they will query the name service before contacting the server. The name service will resolve the name into the corresponding address. If a server process needs to move from one physical server to another, it suffices to update the name to address mapping on the name service to allow all clients to connect to the new server. The name service also enables the servers to better sustain the load. Assume a very popular server which is accessed by millions of users. This service cannot be provided by a single physical server due to performance limitations. Thanks to the utilization of names, it is possible to scale this service by mapping a given name to a set of addresses. When a client queries the name service for the server’s name, the name service returns one of the addresses in the set. Various strategies can be used to select one particular address inside the set of addresses. A first strategy is to select a random address in the set. A second strategy is to maintain information about the load on the servers and return the address of the less loaded server. Note that the list of server addresses does not need to remain fixed. It is possible to add and remove addresses from the list to cope with load fluctuations. Another strategy is to infer the location of the client from the name request and return the address of the closest server.

Mapping a single name onto a set of addresses allows popular servers to dynamically scale. There are also benefits in mapping multiple names, possibly a large number of them, onto a single address. Consider the case of information servers run by individuals or SMEs. Some of these servers attract only a few clients per day. Using a single physical server for each of these services would be a waste of resources. A better approach is to use a single server for a set of services that are all identified by different names. This enables service providers to support a large number of servers processes, identified by different names, onto a single physical server. If one of these server processes becomes very popular, it will be possible to map its name onto a set of addresses to be able to sustain the load. There are some deployments where this mapping is done dynamically in function of the load.

Names provide a lot of flexibility compared to addresses. For the network, they play a similar role as variables in programming languages. No programmer using a high-level programming language would consider using hardcoded values instead of variables. For the same reasons, all networked applications should depend on names and avoid dealing with addresses as much as possible.

Footnotes

- 1

The hosts.txt file is not maintained anymore. A historical snapshot from April 1984 is available from https://www.saildart.org/HOSTS.TXT%5BHST,NET%5D15

- 2

See http://www.donelan.com/dnstimeline.html for a time line of DNS related developments.

- 3

This specification evolved later to support domain names written by using other character sets than us-ASCII RFC 5890. This extension is important to support languages other than English, but a detailed discussion is outside the scope of this document.

- 4

The official list of top-level domain names is maintained by IANA at http://data.iana.org/TLD/tlds-alpha-by-domain.txt Additional information about these domains may be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Internet_top-level_domains

- 5

It is interesting to note that to prevent any homograph attack, Google Inc. registered the g00gle.com domain name but does not apparently use it.

- 6

A copy of the information maintained by each root nameserver is available at http://www.internic.net/zones/root.zone

- 7

Until February 2008, the root DNS servers only had IPv4 addresses. IPv6 addresses were slowly added to the root DNS servers to avoid creating problems as discussed in http://www.icann.org/en/committees/security/sac018.pdf As of February 2021, there remain a few DNS root servers that are still not reachable using IPv6. The full list is available at http://www.root-servers.org/