A closer look at TCP

Contents

A closer look at TCP¶

In this series of exercises, you will explore in more details the operation of TCP and its congestion control scheme. TCP is a very important protocol in today’s Internet since most applications use it to exchange data. We first look at TCP in more details by injecting segments in the Linux TCP stack and analyze how the stack reacts. Then we study the TCP congestion control scheme.

Injecting segments in the Linux TCP stack¶

Packet capture tools like tcpdump and Wireshark are very useful to observe the segments that transport protocols exchange. TCP is a complex protocol that has evolved a lot since its first specification RFC 793. TCP includes a large number of heuristics that influence the reaction of a TCP implementation to various types of events. A TCP implementation interacts with the application through the socket API.

packetdrill is a TCP test suite that was designed to develop unit tests to verify the correct operation of a TCP implementation. A more detailed description of packetdrill may be found in [CCB+2013]. packetdrill uses a syntax which is a mix between the C language and the tcpdump syntax. To understand the operation of packetdrill, we first discuss several examples. The TCP implementation in the Linux kernel supports all the recent TCP extensions to improve its performance. For pedagogical reasons, we disable 1 most of these extensions to use a simple TCP stack. packetdrill can be easily installed on recent Linux kernels 2.

Let us start with a very simple example that uses packetdrill to open a TCP connection on a server running on the Linux kernel. A packetdrill script is a sequence of lines that are executed one after the other. There are three main types of lines in a packetdrill script.

packetdrill executes a system call and verifies its return value

packetdrill injects 3 a packet in the instrumented Linux kernel as if it were received from the network

packetdrill compares a packet transmitted by the instrumented Linux kernel with the packet that the script expects

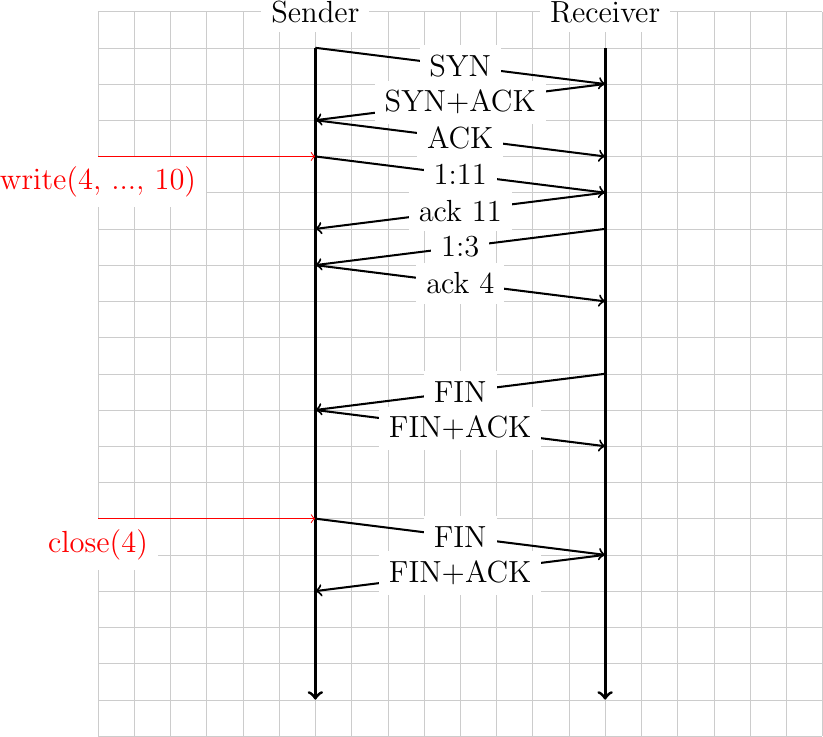

For our first packetdrill script, we aim at reproducing the simple connection shown in the figure below.

Let us start with the execution of a system call. A simple example is shown below.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 3

The 0 indicates that the system call must be issued immediately. packetdrill then executes the system call and verifies that it returns 3`. If yes, the processing continues. Otherwise the script stops and indicates an error.

For this first example, we program packetdrill to inject the segments that a client would send. The first step is thus to prepare a socket that can be used to accept this connection. This socket can be created by using the four system calls below.

// create a TCP socket. Since stdin, stdout and stderr are already defined,

// the kernel will assign file descriptor 3 to this socket

// 0 is the absolute time at which the socket is created

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 3

// Enable reuse of addresses

+0 setsockopt(3, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, [1], 4) = 0

// binds the created socket to the available addresses

+0 bind(3, ..., ...) = 0

// configure the socket to accept incoming connections

+0 listen(3, 1) = 0

At this point, the socket is ready to accept incoming TCP connections. packetdrill needs to inject a TCP segment in the instrumented Linux stack. This can be done with the line below.

+0 < S 0:0(0) win 1000 <mss 1000>

Each line of a packetdrill script starts with a timing parameter that indicates at what time the event specified on this line should happen. packetdrill supports absolute and relative timings. An absolute timing is simply a number that indicates the delay in seconds between the start of the script and the event. A relative timing is indicated by using + followed by a number. This number is then the delay in seconds between the previous event and the current line. Additional information may be found in [CCB+2013].

The description of TCP packets in packetdrill uses a syntax that is very close to the tcpdump one. The +0 timing indicates that the line is executed immediately after the previous event. The < sign indicates that packetdrill injects a TCP segment and the S character indicates that the SYN flag must be set. Like tcpdump, packetdrill uses sequence numbers that are relative to initial sequence number. The three numbers that follow are the sequence number of the first byte of the payload of the segment (0), the sequence number of the last byte of the payload of the segment (0 after the semi-column) and the length of the payload (0 between brackets) of the SYN segment. This segment does not contain a valid acknowledgment but advertises a window of 1000 bytes. All SYN segments must also include the MSS option. In this case, we set the MSS to 1000 bytes. The next line of the packetdrill script verifies the reply sent by the instrumented Linux kernel.

+0 > S. 0:0(0) ack 1 <...>

This TCP segment is sent immediately by the stack. The SYN flag is set and the dot next to the S character indicates that the ACK flag is also set. The SYN+ACK segment does not contain any data but its acknowledgment number is set to 1 (relative to the initial sequence number). For outgoing packets, packetdrill does not verify the value of the advertised window. In this line, it also accepts any TCP options (<...>).

The third segment of the three-way handshake is sent by packetdrill after a delay of 0.1 seconds. The connection is now established and the accept system call will succeed.

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1 win 1000

+0 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

The accept system call returns a new file descriptor, in this case value 4. At this point, packetdrill can write data on the socket or inject packets.

+0 write(4, ..., 10)=10

+0 > P. 1:11(10) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 11 win 1000

packetdrill writes 10 bytes of data through the write system call. The stack immediately sends these 10 bytes inside a segment whose Push flag is set 4. The payload starts at sequence number 1 and ends at sequence number 10. packetdrill replies by injecting an acknowledgment for the entire data after 100 milliseconds.

packetdrill can also inject data that will be read by the stack as shown by the lines below.

+.1 < P. 1:3(2) ack 11 win 4000

+0 > . 11:11(0) ack 3

+.2 read(4,...,1000)=2

In the example above, packetdrill injects a segment containing two bytes. This segment is acknowledged and after that the read system call succeeds and reads the available data with a buffer of 1000 bytes. It returns the amount of read bytes, i.e. 2.

We can now close the connection gracefully. Let us first issue inject a segment with the FIN flag set.

//Packetdrill closes connection gracefully

+0 < F. 3:3(0) ack 11 win 4000

+0 > . 11:11(0) ack 4

packetdrill injects the FIN segment and the instrumented kernel returns an acknowledgment. If packetdrill issues the close system call, the kernel will send a FIN segment to terminate the connection. packetdrill injects an acknowledgment to confirm the end of the connection.

+0 close(4) = 0

+0 > F. 11:11(0) ack 4

+0 < . 4:4(0) ack 12 win 4000

The complete packetdrill script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/connect.pkt.

Another interesting features of packetdrill is that it is possible to inspect the state maintained by the Linux kernel for the underlying connection using the TCP_INFO socket option. This makes it possible to retrieve the value of some variables of the TCP control block.

Let us first explore how a TCP connection can be established. In the previous script, we have injected the segments that a client would send to a server. We can also use the Linux stack as a client and inject the segments that a server would return. Such a client process would first create its socket` and then issue the connect system call. At this point, the stack sends a SYN segment. To simplify the scripts, we have configured the stack to use a MSS of 1000 bytes and disabled the TCP extensions (the details of this configuration may be found at the beginning of the script). The server replies with a SYN+ACK and the stack sends acknowledges it to finish the three-way-handshake.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

+0 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

+0 setsockopt(4, SOL_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, [1], 4) = 0

+0 connect(4, ..., ...) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

+0 > S 0:0(0) <mss 1000>

// TCP State is now SYN_SENT

+0 %{ print "State@1", tcpi_state }% // prints 2, i.e. TCP_SYN_SENT

+.1 < S. 0:0(0) ack 1 win 10000 <mss 1000>

+0 > . 1:1(0) ack 1

+0 %{ print "State@2", tcpi_state }% // prints 1, i.e. TCP_ESTABLISHED

// TCP State is now ESTABLISHED

The tcpi_state variable used in this script is returned by TCP_INFO 5. It tracks the state of the TCP connection according to TCP’s finite state machine 6. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/client.pkt.

Another example is the simultaneous establishment of a TCP connection. The TCP stack sends a SYN and receives a SYN in response instead of a SYN+ACK. It then acknowledges the received SYN and retransmits its own SYN. The connection becomes established upon reception of the fourth segment.

This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/dual.pkt.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

+0 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

+0 setsockopt(4, SOL_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, [1], 4) = 0

+0 connect(4, ..., ...) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

+0 > S 0:0(0) <mss 1000>

+0 %{ print "State@1", tcpi_state }% // prints 2, i.e. TCP_SYN_SENT

+.1 < S 0:0(0) win 5792 <mss 1000>

+0 %{ print "State@2", tcpi_state }% // prints 3, i.e. TCP_SYN_RECV

+0 > S. 0:0(0) ack 1 <mss 1000>

+0 %{ print "State@3", tcpi_state }% // prints 3, i.e. TCP_SYN_RECV

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1 win 5792

+0 %{ print "State@4", tcpi_state }% // prints 1, i.e. TCP_ESTABLISHED

Another usage of packetdrill is to explore how a TCP connection ends. The scripts below show how a TCP stack closes a TCP connection. The first example shows a local host that connects to a remote host and then closes the connection. The remote host acknowledges the FIN and later closes its direction of data transfer. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/local-close.pkt.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

+0 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

+0 setsockopt(4, SOL_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, [1], 4) = 0

+0 connect(4, ..., ...) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

+0 > S 0:0(0) <mss 1000>

+.1 < S. 0:0(0) ack 1 win 10000 <mss 1000>

+0 > . 1:1(0) ack 1

+.1 close(4)=0

+0 > F. 1:1(0) ack 1

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2 win 10000

+.1 < F. 1:1(0) ack 2 win 10000

+0 > . 2:2(0) ack 2

As for the establishment of a connection, it is also possible for the two communicating hosts to close the connection at the same time. This is shown in the example below where the remote host sends its own FIN when acknowledging the first one. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/local-close2.pkt.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

+0 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

+0 setsockopt(4, SOL_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, [1], 4) = 0

+0 connect(4, ..., ...) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

+0 > S 0:0(0) <mss 1000>

+.1 < S. 0:0(0) ack 1 win 10000 <mss 1000>

+0 > . 1:1(0) ack 1

+.1 close(4)=0

+0 > F. 1:1(0) ack 1

+.1 < F. 1:1(0) ack 2 win 10000

+0 > . 2:2(0) ack 2

A third scenario for the termination of a TCP connection is that the remote hosts sends its FIN first. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/remote-close.pkt.

0 socket(..., SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

+0 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

+0 setsockopt(4, SOL_TCP, TCP_NODELAY, [1], 4) = 0

+0 connect(4, ..., ...) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

+0 > S 0:0(0) <mss 1000>

+.1 < S. 0:0(0) ack 1 win 10000 <mss 1000>

+0 > . 1:1(0) ack 1

// remote closes

+.1 < F. 1:1(0) ack 1 win 10000

+0 > . 1:1(0) ack 2

// local host terminates the connection

+.1 close(4)=0

+0 > F. 1:1(0) ack 2

+0 < . 2:2(0) ack 2 win 10000

Another very interesting utilization of packetdrill is to explore how a TCP stack reacts to acknowledgments that would correspond to lost or reordered segments. For this analysis, we configure a very large initial congestion window to ensure that the connection does not start with a slow-start.

Let us first use packetdrill to explore the evolution of the TCP retransmission timeout. The value of this timeout is set based on the measured round-trip-time and its variance. When the retransmission timer expires, TCP doubles the retransmission timer. This exponential backoff mechanism is important to ensure that TCP slowdowns during very severe congestion periods. We use the tcpi_rto variable from TCP_INFO to track the evolution of the retransmission timer. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/rto.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 16KBytes

// server sends 8000 bytes

+0 %{ print "RTO @1: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 204000 (microseconds)

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

// client acks one segment

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "RTO @2: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 216000 (microseconds)

// client did not receive any other segment

// first server retransmissions

+.216 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 %{ print "RTO @3: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 432000 (microseconds)

// second after doubling rto

+.432 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 %{ print "RTO @4: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 864000 (microseconds)

+.864 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 %{ print "RTO @5: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 1728000 (microseconds)

We can use a similar code to demonstrate that the TCP stack performs a fast retransmit after having received three duplicate acknowledgments. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/frr.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 16KBytes

// server sends 8000 bytes

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @1: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 0

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

// client acks two segments

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// server retransmits after three duplicate acks

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// client acks everything

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @2: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 1000

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

A TCP stack uses both the fast retransmit technique and retransmission timers. A retransmission timer can fire after a fast retransmit when several segments are lost. The example below shows a loss of two consecutive segments. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/frr-rto.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 16KBytes

// server sends 8000 bytes

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @1: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }%

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

// client acks one segments

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// server retransmits after three duplicate acks

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// client acks retransmission

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @2: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 1000

+0 %{ print "RTO @2: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 224000

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 3001 win 50000

+.024 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

// client acks everything

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

More complex scenarios can be written. The script below demonstrates how the TCP stack behaves when three segments are lost. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/frr-rto2.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 16KBytes

// server sends 8000 bytes

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @1: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }%

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

// client acks first two segments

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// server retransmits after three duplicate acks

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

// client acks retransmission

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @2: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 1000

+0 %{ print "RTO @2: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 224000

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 4001 win 50000

+.024 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

// client acks block

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @3: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 2000

+0 %{ print "RTO @3: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 224000

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+.024 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

// client acks block

+0 %{ print "retransmissions @3: ",tcpi_bytes_retrans }% // prints 3000

+0 %{ print "RTO @3: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 224000

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

The examples above have demonstrated how TCP retransmits lost segments. However, they did not consider the interactions with the congestion control scheme since the use a large initial congestion window. We now set the initial congestion window to two MSS-sized segments and use the tcpi_snd_cwnd and tcpi_snd_ssthresh variables from TCP_INFO to explore the evolution of the TCP congestion control scheme. Our first script looks at the evolution of the congestion window during a slow-start when there are no losses. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/slow-start.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 2 KBytes

+0 %{ print "cwnd @1: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @1: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2147483647

// server sends 16000 bytes

+.1 write(4, ..., 16000) = 16000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @2: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @3: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 3001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @4: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 5

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 4001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @5: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 6

+0 > . 8001:9001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 9001:10001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 5001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @6: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 7

+0 > . 10001:11001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 11001:12001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @7: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 8

+0 > . 12001:13001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 13001:14001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 7001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @8: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 9

+0 > . 14001:15001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 15001:16001(1000) ack 1

// client acks everything

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 16001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @9: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 18

Some TCP clients use delayed acknowledgments and send a TCP acknowledgment after after second in-sequence segment. This behavior is illustrated in the script below. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/slow-start-delayed.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 2 KBytes

+0 %{ print "cwnd @1: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @1: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2147483647

// server sends 16000 bytes

+.1 write(4, ..., 16000) = 16000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @2: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 4001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @4: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 6

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 8001:9001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 9001:10001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @6: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 8

+0 > . 10001:11001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 11001:12001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 12001:13001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 13001:14001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @8: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 10

+0 > . 14001:15001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 15001:16001(1000) ack 1

// client acks everything

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 16001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @9: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 18

We can now explore how TCP’s retransmission techniques interact with the congestion control scheme. The Linux TCP code that combines these two techniques contains several heuristics to improve their performance. We start with a transfer of 8KBytes where the penultimate segment is not received by the remote host. In this case, TCP does not receive enough acknowledgments to trigger the fast retransmit and it must wait for the expiration of the retransmission timer. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/slow-start-rto2.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 2 KBytes

+0 %{ print "cwnd @1: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @1: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2147483647

// server sends 8000 bytes

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @2: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 2001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @3: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 3001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @4: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 5

+0 %{ print "RTO @4: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 252000

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 4001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @5: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 6

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 5001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @6: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 7

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @7: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 8

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @8: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 8

+.25 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1 // retransmission

+0 %{ print "cwnd @9: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 1

+.1 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @10: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

Another interesting scenario is when the loss happens early in the data transfer. This is shown in the script below where the second segment is lost. We observe that by triggering transmissions of unacknowledged data, the RFC 3042 rule speeds up the recovery since a fast retransmit happens. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/slow-start-frr2.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 2 KBytes

+0 %{ print "cwnd @1: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @1: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2147483647

// server sends 8000 bytes

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @2: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

+0 %{ print "RTO @2: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 204000

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000 // reception of 2001:3001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @3: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1 // rfc 3042

+0.001 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000 // reception of 3001:4001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @4: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 3

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1 // rfc 3042

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000 // reception of 4001:5001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @5: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @5: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2

// fast retransmit

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+0.001 < . 1:1(0) ack 1001 win 50000 // reception of 5001:6001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @6: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1 // rfc 3042

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000 // reception of 1001:2001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @7: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @7: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 7001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @7: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

+0.001 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @8: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 5

Our last scenario is when the first segment sent is lost. In this case, two round-trip-times are required to retransmit the missing segment and recover from the loss. This script is available from /exercises/packetdrill_scripts/slow-start-frr3.pkt.

+.1 accept(3, ..., ...) = 4

// initial congestion window is 2 KBytes

+0 %{ print "cwnd @1: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 %{ print "ssthresh @1: ",tcpi_snd_ssthresh }% // prints 2147483647

+0 %{ print "RTO @1: ",tcpi_rto }% // prints 204000

// server sends 8000 bytes

+.1 write(4, ..., 8000) = 8000

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1 // lost

+0 > . 1001:2001(1000) ack 1

+.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1 win 50000 // duplicate ack

+0 %{ print "cwnd @2: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 > . 2001:3001(1000) ack 1 // rfc3042

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1 win 50000 // reception of 2001:3001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @3: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 > . 3001:4001(1000) ack 1 // rfc3042

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 1 win 50000 // reception of 3001:4001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @4: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 1

// fast retransmit

+0 > . 1:1001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 4001 win 50000 // reception of 1:1001

+0 %{ print "cwnd @5: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 2

+0 > . 4001:5001(1000) ack 1

+0 > . 5001:6001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 6001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @6: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

+0 > . 6001:7001(1000) ack 1

+0 > P. 7001:8001(1000) ack 1

+0.01 < . 1:1(0) ack 8001 win 50000

+0 %{ print "cwnd @7: ",tcpi_snd_cwnd }% // prints 4

Open questions¶

Unless otherwise noted, we assume for the questions in this section that the following conditions hold.

the sender/receiver performs a single send(3) of x bytes

the round-trip-time is fixed and does not change during the lifetime of the TCP connection. We assume a fixed value of 100 milliseconds for the round-trip-time and a fixed value of 200 milliseconds for the retransmission timer.

the delay required to transmit a single TCP segment containing MSS bytes is small and set to 1 milliseconds, independently of the MSS size

the transmission delay for a TCP acknowledgment is negligible

the initial value of the congestion window is one MSS-sized segment

the value of the duplicate acknowledgment threshold is fixed and set to 3

TCP always acknowledges each received segment

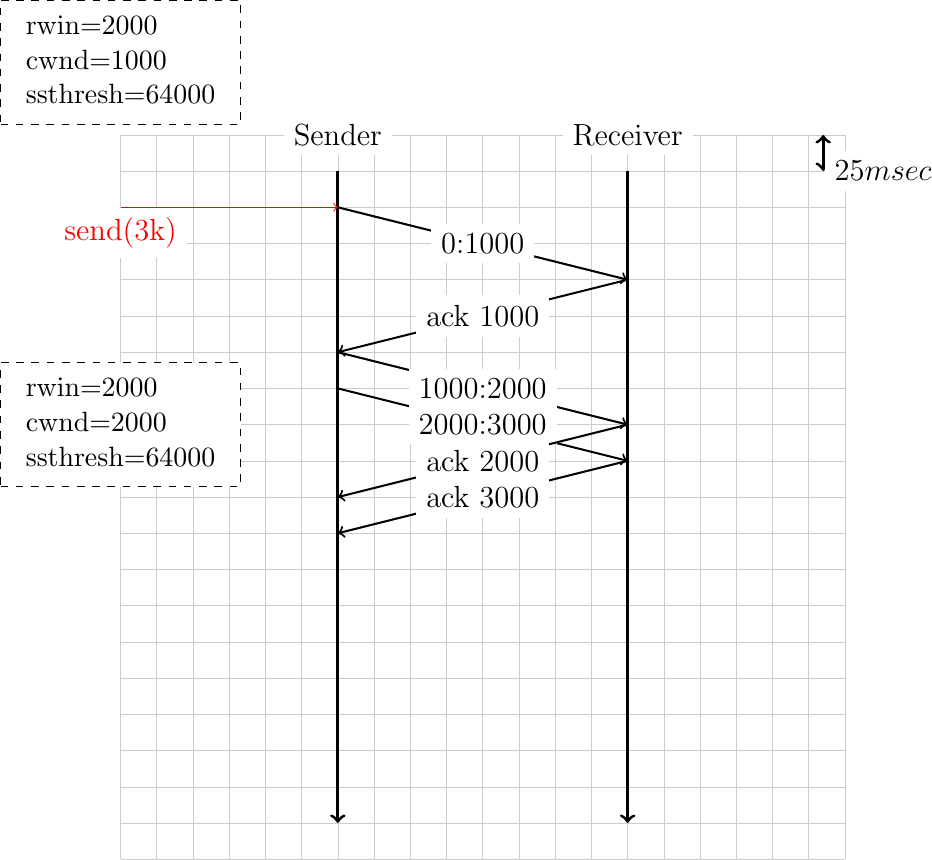

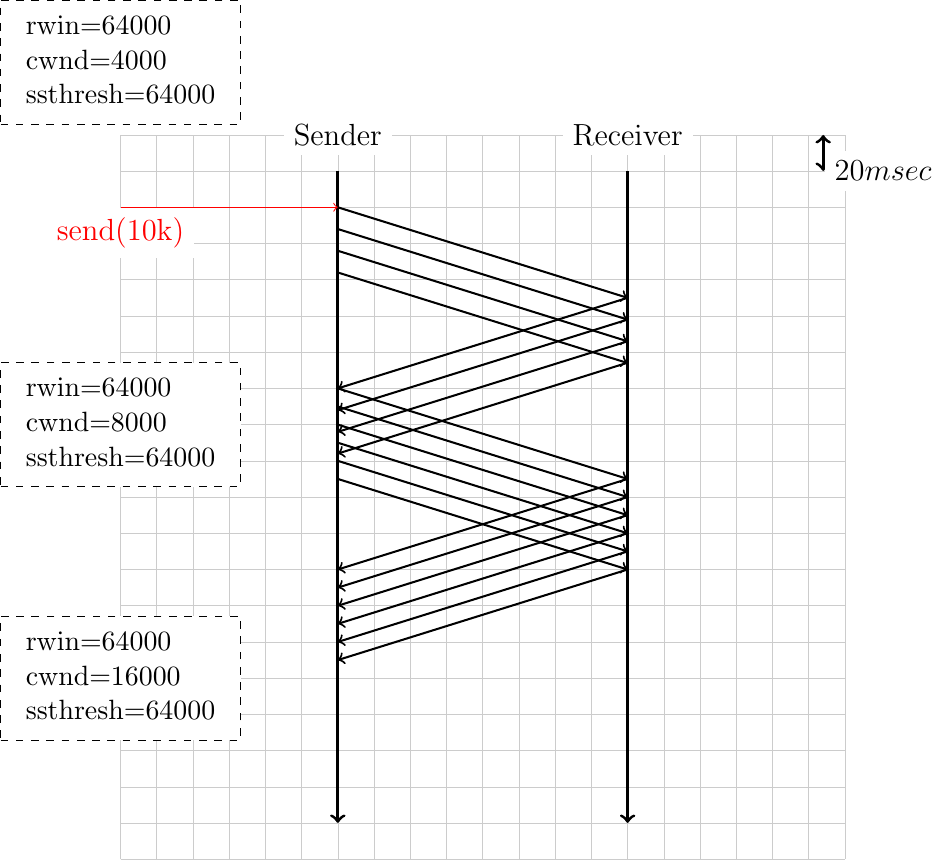

To understand the operation of the TCP congestion control, it is often useful to write time-sequence diagrams for different scenarios. The example below shows the operation of the TCP congestion control scheme in a very simple scenario. The initial congestion window (

cwnd) is set to 1000 bytes and the receive window (rwin) advertised by the receiver (supposed constant for the entire connection) is set to 2000 bytes. The slow-start threshold (ssthresh) is set to 64000 bytes.

Can you explain why the sender only sends one segment first and then two successive segments (the delay between the two segments on the figure is due to graphical reasons) ?

Can you explain why the congestion window is increased after the reception of the first acknowledgment ?

How long does it take for the sender to deliver 3 KBytes to the receiver ?

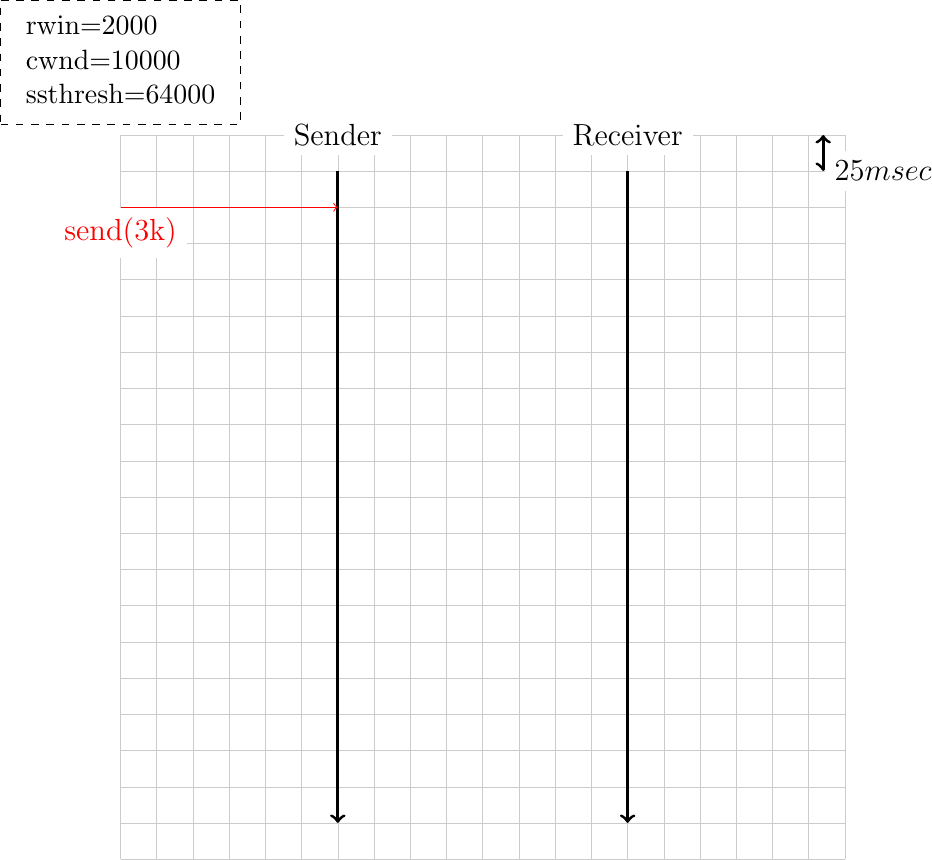

Same question as above but now with a small variation. Recent TCP implementations use a large initial value for the congestion window. Draw the time-sequence diagram that corresponds to an initial value of 10000 bytes for this congestion window.

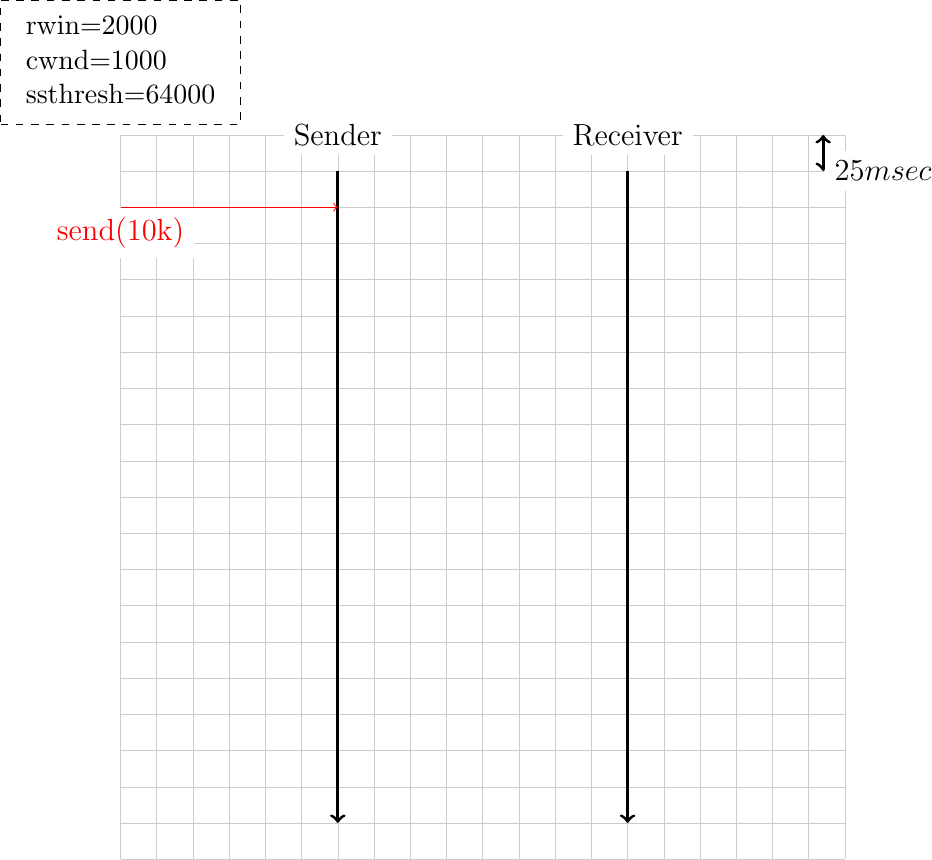

Same question as the first one, but consider that the MSS on the sender is set to 500 bytes. How does this modification affect the entire delay ?

Assuming that there are no losses and that there is no congestion in the network. If the sender writes x bytes on a newly established TCP connection, derive a formula that computes the minimum time required to deliver all these x bytes to the receiver. For the derivation of this formula, assume that x is a multiple of the maximum segment size and that the receive window and the slow-start threshold are larger than x.

In question 1, we assumed that the receiver acknowledged every segment received from the sender. In practice, many deployed TCP implementations use delayed acknowledgments. Assuming a delayed acknowledgment timer of 50 milliseconds, modify the time-sequence diagram below to reflect the impact of these delayed acknowledgment. Does their usage decreases or increased the transmission delay ?

Let us now explore the impact of congestion on the slow-start and congestion avoidance mechanisms. Consider the scenario below. For graphical reasons, it is not possible anymore to show information about the segments on the graph, but you can easily infer them.

Redraw the same figure assuming that the second segment that was delivered by the sender in the figure experienced congestion. In a network that uses Explicit Congestion Notification, this segment would be marked by routers and the receiver would return the congestion mark in the corresponding acknowledgment.

Same question, but assume now that the fourth segment delivered by the sender experienced congestion (but was not discarded).

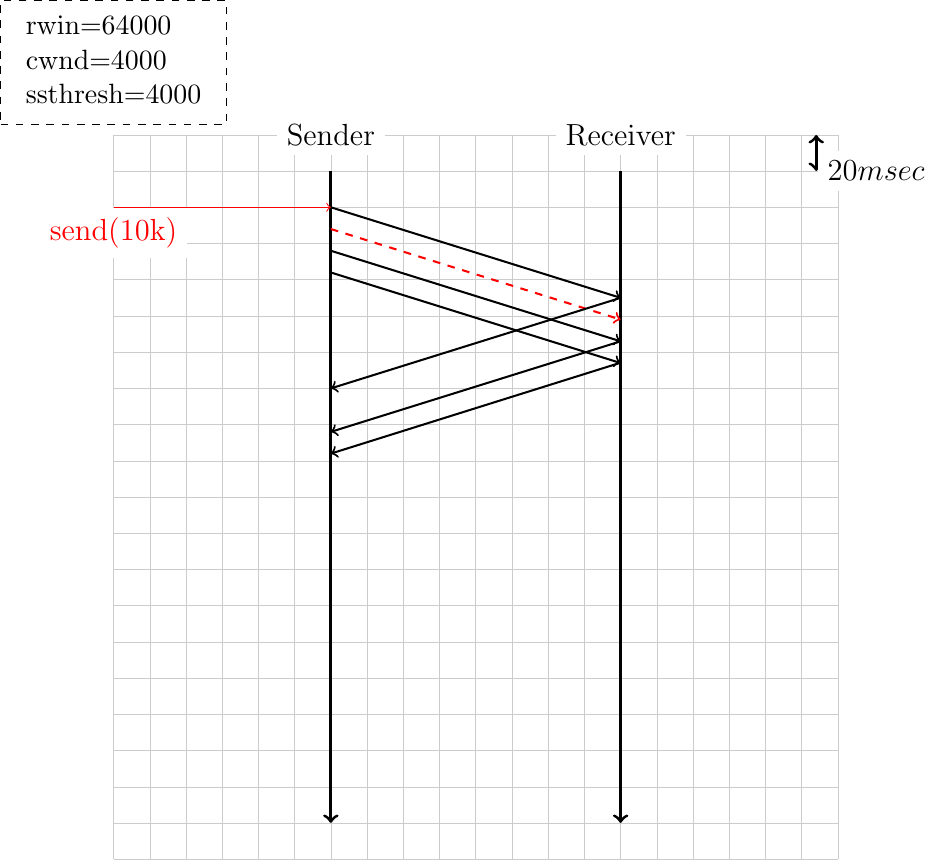

A TCP connection has been active for some time and has reached a congestion window of 4000 bytes. Four segments are sent, but the second (shown in red in the figure) is corrupted. Complete the time-sequence diagram.

Footnotes

- 1

On Linux, most of the parameters to tune the TCP stack are accessible via sysctl. These parameters are briefly described in https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/Documentation/networking/ip-sysctl.rst and in the tcp manpage. Each script sets some of these configuration variables.

- 2

packetdrill requires root privileges since it inject raw IP packets. The easiest way to install it is to use a virtualbox image with a Linux kernel 4.x or 5.x. You can clone its git repository from https://github.com/google/packetdrill and follow the instructions in https://github.com/google/packetdrill/tree/master/gtests/net/packetdrill. The packetdrill scripts used in this section are available from https://github.com/cnp3/ebook/tree/master/exercises/packetdrill_scripts

- 3

By default, packetdrill uses port 8080 when creating TCP segments. You can thus capture the packets injected by packetdrill and the responses from the stack by using

tcpdump -i any -n port 8080- 4

The Push flag is one of the TCP flags defined in RFC 793. TCP stacks usually set this flag when transmitting a segment that empties the send buffer. This is the reason why we observe this push flag in our example.

- 5

The variables that are included in TCP_INFO are defined in https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/uapi/linux/tcp.h

- 6

These states are defined in https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/include/net/tcp_states.h